Rumour has it that you were a med student who changed majors to film, before later enrolling at UCLA. How did you first develop an interest in filmmaking and what kind of projects were you working on during those early years?

“I was a pre-med student at Stephen F Austin University in Nacogdoches, Texas. My doctor uncle did his pre-med there. They are recognized for their School of Forestry and the sports teams are the Lumberjacks. Maybe that’s why I dared to GO IN THE WOODS and am proud to say,even now – “I’m a lumberjack and I’m okay!” My early film interest in filmmaking developed with my family’s enjoyment of films. I really liked Disney films, westerns with Roy Rogers and Abbot and Costello comedies. I would laugh so long and loud others of the audience would complain to my parents. I took over the family’s 8mm camera and started shooting little bits of film. The local drug store and film processing counter had film cement but no splicers so I used a pair of pliers to do my first editing. The pliers had grooves for gripping so the cement splice produced a sort of ripple effect on all my cuts. 8mm splicing tape became available around that time and in high school I cast friends in a number of longer film shorts.”

What can you reveal about your earlier erotic features, such as Escape to Passion and The Dirtiest Game. What convinced you to try that route into the industry and in which ways do you feel they prepared you for your later work?

“I really wanted to make a feature film after doing shorts and documentaries at the UCLA Film School. Escape to Passion and Dirtiest Game were my first features following the low budget rules Roger Corman set forth in various interviews. On a limited budget with a primary schedule of three days (not counting pickup shots) you could get a commercial project of a theatrical type if you had at least 10 exploitation (action or sex) scenes each occurring no more than 10 minutes apart. “One thrill a reel (10 minutes)” was Corman’s motto as I recall. My thought was that with 10 sex scenes for an erotic film I could do anything else I wanted to do as far as the rest of the story went. Dirtiest Game tested the limits of what a adult film audience would endure. My goal was to inflame or repulse the people who happened to be in the audience. It was successful in that many people left the theatre but did not stop to ask for their money back. Only one patron became physically ill as far as I heard from the distributor. It had a political story line and it was very popular in Washington DC where a bar near the capital bought a 16mm print and ran it every night until the print fell apart. It took about a year. The film was very gross and so had a limited appeal. Most of my friends after seeing the film didn’t speak to me for about a month. Escape to Passion was my attempt to do an adult film that with minor edits could pay in regular drive ins and in addition, not endanger any friendships. It was a gangster film that had more action and plenty of comedy that ended with a police shootout at a Crisco orgy. Also it had a song or two. It did play drive ins and nobody threw up or ran out of the theatre. The production schedule doubled with more story and action added. I learned the wisdom of doing low budget films in a series of three day interrupted schedules which would allow some rest, recovery and some added preparation, otherwise the naturally occurring problems and stress would overwhelm a small crew.”

How come you decided to move from comedy with Boogie Vision to producing a low budget horror movie?

“Crest Films was distributing Boogie Vision nationally and it was doing so-so business when Universal approached them with major funding to distribute Kentucky Fried Movie on an exclusive basis. Boogie Vision was dropped and I decided to do the distribution myself since nobody else wanted to take it on. When I finished going bankrupt and recovering in Utah working post production at Sunn Classic, horror films were popular with audiences once more, so I set out to do a horror film that could have national distribution and I was more or less successful.”

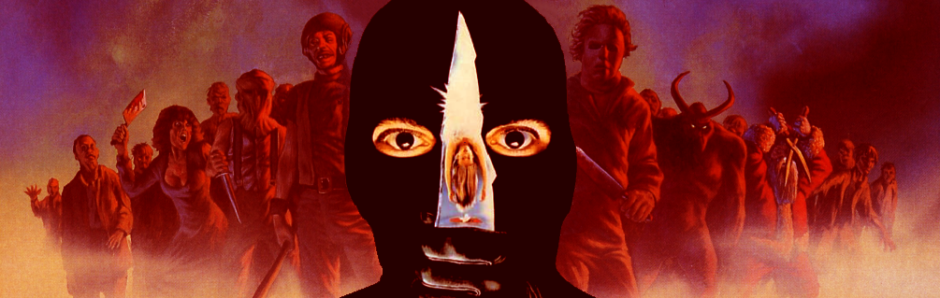

How did the initial concept for Don’t Go in the Woods come about and which films or stories were an influence on you during the writing of the script? Was it always your intention to make a slasher film or was your original vision substantially different?

“In Salt Lake City my post production work with Sunn Classic was drawing to a close, the NBC production contracts were coming to an end for Sunn Classic as Paul Klien, NBC president and chief supporter of Sunn Classic, was finishing his association with the network. Sunn Classics went up for sale but its stock and trade, the local Utah scenic beauty, was still available to all low budget filmmakers craving affordable production value. Inspiration was gushing forth all around the mountain community. In the book stores an urban legend book by a Salt Lake writer had just come out, a wild man legend from my East Texas roots was gnawing away consistently at the back of my mind and the local Salt Lake stories of hikers sometimes murdered in the surrounding mountains started to play into the mix. I had just read a stripped down paperback thriller called Hunters Moon and elements of a potential script started to come into a very soft focus. It was at this moment an old friend Peter Turner, a writer’s agent from LA, called asking what I was up to. When I said I was thinking about developing a horror script, Peter snapped back, “Save yourself the trouble, I’m sending you one that’s already perfect.” That script was Sierra by Garth Eliassen and it did happen to be almost perfect. I did a quick rewrite with Garth to fit the new location, the new budget (very low) and added more bloody killing scenes while dropping almost all the existing dialogue scenes. I had a plan. I would shoot outside for daylight avoiding having to light the set except for the few night scenes and use my unblimped 35mm Arri recording only a scratch sound track. By limiting the sync dialogue to a minimum amount it would be simpler and cheaper to replace in a sound studio. As the seventies drew to a close, I was thinking lots of blood and gore in the Misumi Kenji Sword of Vengeance-style and a touch of humor would do the trick. So I took it to the woods and did it my way. I would say Woods was as I intended it bloody and yet with an element of humor.”

Who was Peter Turner and what part did he play in the making of the movie? How was the project funded and what kind of budget were you working with?

“When I finished at Sunn Classic I had put back some money, enough to get me thru production. With the film in the can I held off sending it to the lab until Roberto and Suzette Gomez came on board as producers funding the next stage. I used credit to get the answer print for Woods and that allowed me to find a distributor who paid off the lab thru a series of deals for VHS and foreign rights. The total budget ended up around $150,000.”

Is it true that the entire film stock that you used to shoot the movie was about to be recycled and so you were able to purchase it considerably cheaper?

“The film stock was short ends that were out of date and slated to be reclaimed for the silver. I paid under $400 and took a big chance which DeLuxe Labs was able to pay off on when they expertly corrected the fading color into a nice inter negative.”

How did you cast for the film and were you already familiar with many of your collaborators prior to commencing work on Don’t Go in the Woods? With most of them rarely appearing in film or television after 1981, were any professional actors?

“The mood on the set of Don’t Go in the Woods changed wildly from day to day. Just as the weather snapped from one extreme to another, one scene might go along like a summer picnic with old friends and then we’d find ourselves in something like a Werner Herzog-Klaus Kinski dogfight over creative differences. All our problems were ultimately resolved fairly quickly and we kept moving on our most sacred production schedule. Things happened at a fast clip so actors often seemed a little lost as to a scene’s place in the story. The good actors quickly adapted to my manic vision and by the final days of the shoot we were reading each other’s mind anticipating the blocking and bits of physical business. The theatre scene in Salt Lake City was pretty well developed so as a director I was able to get really professional results with a few notable exceptions. You know the ones, we need not name names. Ken Carter was a DJ from Texas who had been in my high school 8mm short films and very much wanted to play the Sheriff. Frank Millen I knew from UCLA Film School and who appeared in almost every film I did.”

How did Tom Drury become involved and how did you first make his acquaintance? As he was already a singer at that point, was he also an actor or was Don’t Go in the Woods his first appearance?

“I met Tom Drury when working for a local Salt Lake City producer on a VHS series. Tom did theatre locally, did a few USO tours in Southeast Asia singing with his wife and had some Daniel Boone TV series exposure. The hikers were recruited by Peter Turner and had appeared in minor parts in Boogie Vision. The LA cast all worked in the film business. When Tom Drury had a work conflict during our on and off two week schedule I doubled him as the maniac in the off angles and long shots. Running the show as producer and director is so overwhelming the idea of being an actor as well is beyond reason.”

Whereabouts in Utah was the movie shot and what kind of schedule did you have? What were the main obstacles you had to overcome in order to make the shoot run as smoothly as possible?

“We shot everything east and south of Salt Lake City in the Watsch Mountians mainly in Lambs Canyon where the Cabin is located. The Stockdale cabin was our production base. We used the three days on-one day off schedule for the main cast of hikers. The other victims were shot before and after the main schedule on weekends, one victim and location at a time, using the Lambs canyon base. If you don’t have a big budget you had better know who to go to find what you need for your production.”

For the special effects, you chose your then-wife, Kathie Bryan, as your makeup artist. Was she experienced at designing gruesome effects or was this an effort to keep the cost to a minimum?

“Kathie was involved in those high school 8mm projects as well and besides working in the drama club there, her college art major and background in painting and sculpture gave her plenty of experience and training to draw on for the make up and effects challenge in Woods. Kathie and I did some dinosaur animation together for a National Geographic TV show early on. Kathie did the blood. Kraft BBQ sauce (non-chunky) with Red dye #2 worked best. It coagulated like blood does and was okay to swallow. The spicy nature was a problem for some actors who had to hold it in their mouths over several takes due to the stinging and burning of the spices and vinegar.”

How come you chose to dub the movie during post-production and were you pleased with the results?

“Starting with Lady Street Fighter, I began the using the Italian low budget approach to production, shooting without sync sound. If you have a background in dialogue replacement and know how much it’s used on TV shows and films, it’s easy to see it is a good way of saving money. By recording a sound track without the expense of a blimped or a sound deadened camera on location you can ignore airplanes, traffic and boom or mike noise that ruin so many takes and cause endless delays. Sunn Classic dubbed almost all their scenes for performance. Well known professionals get paid minimum wages, union scale, when they replace dialogue in a studio far from locations and they also play multiple parts since they aren’t seen. If your studio has limited electronics the recording quality can’t be adjusted so finely that you can’t tell the difference between dubbed and non dubbed dialogue. Woods re-mastered 25 years later for DVD had it’s sound improved to an amazing degree by the advanced electronics that are today standard in almost all video sound equipment. The original quality was disappointing in the extreme but the solution was beyond the limits of the rock bottom budget.”

Don’t Go in the Woods boasts a bizarre score, much different to the standard slasher style. Did you have a specific style in mind as you were shooting and how specific were you with your composer about what you wanted?

“The score was a grand experiment. The composer H Kingsley Thurber worked on industrial projects in Salt Lake City and began in that vein when he started to work on Woods. In our meeting after the first recording session I explained a starting point for the score should be John Carpenter’s approach for Halloween and then for Kingsley to go as far as he could push himself into original musical territory. Anything possible that he could get on tape was just what I wanted to hear. And I loved it. The Woods song was a separate tape done as a joke for my ears alone but it caught the spirit I was trying to follow so I just had to use it for the titles.”

How do you feel about the treatment that the movie received in the UK, with it being subsequently banned as a ‘video nasty’ during the eighties? Were you surprised by this reaction and what do you think was the main cause for this?

“I always wanted to entertain on the verge of offending so I was tickled to be so well received in the UK. I was of course surprised that anybody would be so morally threatened by Woods that the government would become involved.”

The film has often been referred to as ‘so bad it’s good,’ due to its camp nature and inept acting. Do you feel this is a fair statement and what are your own thoughts on the movie?

“Later in high school and college independent low budget films really caught my attention. Italian sword and sandal epics or anything from American International Pictures had me racing to the theatres where I was talking back to the screen, making dumb jokes and attempting to improve the dialogue and story lines with my solo surreal commentaries. The Roger Corman horror films were the best. That life changing paradigm shift came crashing down in a screening of The Terror with the realization that Jack Nicholson was actually playing the character of an incredibly bad miscast actor with a terribly inappropriate accent in the middle of this Vincent Price horror film. This was art! “Bad” could be great. And so began my long search for the aesthetic of the “Bad.” Jack N being goofy again in Easy Rider seeming not to be acting, Val Lewton stretching his budget with affecting moments of what was not seen, and Orson Welles pulling us into that “other” world in Touch of Evil all helped put me on the road to Don’t Go In The Woods.”

Over the years, were you proud of what you had achieved with Don’t Go in the Woods and at what point did you realise that it had become a cult classic?

“When Don’t Go in the Woods first came out audience reaction was very limited. The movie sort of faded from the screen without much notice. While The Hollywood Reporter reviewed it as the worst film ever made even that questionable distinction was all too easily lost when the very next day another opening film replaced Woods as “worst ever.” In light of Woods current newfound interest and popularity, my feeling about the film is that it’s like telling a joke where the audience just shrugs and walks out, then thirty years later they stop what they are doing and all start laughing. A long wait but the laughter lives. Was it something I did? I didn’t realize Woods had become a cult classic until Steven Thrower contacted me for a series of interviews that were to be part of his Nightmare USA , slowly the light dawned.”

Have you ever considered directing a sequel or remake and have you ever heard of any studio or producer expressing interest in making one?

“Yes, I have recently been approached by a number of persons inquiring about a sequel or sequels. Anything can happen. That’s all I can say at this point.”

7 Responses to Exclusive DON’T GO IN THE WOODS Interview: James Bryan