Director: Romano Scavolini

Writer: Romano Scavolini

Starring: Baird Stafford, Sharon Smith, C.J. Cooke, Mik Cribben

Vile, disgusting, amateur, preposterous, exploitation. Romano Scavolini’s 1981 notorious splatter effort Nightmare has been described as many things, often referred to as misogynistic, usually in the same breath as William Lustig’s Maniac and Lucio Fulci’s New York Ripper. The tale of a deranged killer’s supposed rehabilitation into society, resulting in a gruesome killing spree from New York to Florida, Nightmare was a a surreal blend of art house and slasher, attempting to create an allegory on forced conformity in much the same way as Stanley Kubrick’s equally reviled A Clockwork Orange. The eighties saw a succession of low budget sickfests that would fall foul of both censors and critics, with many – such as Ulli Lommel’s The Boogeyman, Abel Ferrara’s The Driller Killer and, of course, Nightmare (more commonly referred to as Nightmare in a Damaged Brain) – finding their way onto the notorious ‘video nasty’ list in Great Britain. But whereas many of its contemporaries (The Dorm That Dripped Blood, Don’t Go in the Woods) failed to live up to the hype, what Nightmare may have lacked in style and subtlety it more than boasted in excess and bloodshed.

The Video Recordings Act 1984, which had been created by the Directors of Public Prosecutions (DPP) to combat the rise in questionable material that had materialised in the dawn of the home video, would eventually target any film which they considered morally offensive and would result in the horror and exploitation genres coming under fire from moral watchdogs and tabloid newspapers. The three main type of films to be targeted were either of Italian origin (Twitch of the Death Nerve, The House by the Cemetery, Cannibal Holocaust), a concoction of sex and violence (The Last House on the Left, I Spit on Your Grave) or simply a showcase for elaborate special effects (Dead and Buried, The Burning). Nightmare succeeded in falling into all three categories. Not only would the movie become the subject of much debate, but the director himself was heavily criticised for the film’s portrayal of mental illness and sexual violence.

The origin of Nightmare had been conceived in 1974 when Italian-born director Scavolini happened upon an article in The New York Times which revealed details about a CIA mind control research program entitled MK-Ultra. First created in the fifties, the program was run by the Office of Scientific Intelligence, eventually abandoned in the late sixties. The article detailed the key aspects of MK-Ultra, focusing on the governments decision to use various drugs on convicts and mental patients in order to manipulate their mental state. In 1975, the US congress and the Rockefeller Commission launched an investigation into the mistreatment of the program’s subjects, revealing CIA director Richard Helms’ orders to have all files on MK-Ultra destroyed two years earlier. It is somewhat ironic that it would be The New York Times that would plant the seed for what was to become Nightmare, as seven years later one of their writers, Janet Maslin, would be the most vocal in her disgust with the movie. Scavolini’s treatment would attract the attention of New York broker David Jones, who had earned a fortune on the gold market and had chosen to establish a production company, the aptly named Goldmine Productions.

Nightmare, or Dark Games as it first went into production as, told of a disturbed young man, George Tatum, who had brutally murdered his mother and her lover with an axe when he was a child. Having spent years in a mental hospital, constantly subjected to medical experimentation, George has been plagued by nightmares on that fateful night and often wakes up screaming. With his doctors eventually deciding that he has been suitably rehabilitated, he is released back into society, immediately finding it difficult to cope with the outside world. George spends his first evening populating various strip clubs and sex shows (including a dildo performance from Tara Alexander, who once held the distinction of having sex with the most men in one session, eventually being outdone by Annabel Chong in 1995) in and around Times Square, the same sleazy New York audiences were subjected to with Taxi Driver and Basket Case. Meanwhile, a new family have taken residence in his old home, with one of the children being the token practical joker that have populated the genre since the success of Friday the 13th. George, unable to deal with his recurring visions, decides to make his way back to Florida, leaving a trail of corpses in his wake. But can his doctors find him before he claims another family and finally descends into madness for good?

Nightmare, much like Maniac, attempted to humanise its disturbed antagonist, as opposed to the cardboard cut outs that usually dominate the slasher film, such as Jason Voorhees and Michael Myers. Scavolini ordered for the Nightmare to be edited four times before being satisfied, insisting to Jones that the graphic violence was an essential part of the story and should not be watered down. The movie eventually made its debut on October 23 1981 in New York to little fanfare, becoming lost among the more mainstream efforts of the year (Friday the 13th Part 2, My Bloody Valentine, The Burning). But in the UK, horror films were the subject of much debate, mainly due to the moral spokeswoman Mary Whitehouse. VIPCO had prepared for their release of The Driller Killer by publishing a full-page add of the movie’s now-infamous posted or a man with a drill through his forehead, resulting in the Advertising Standards Agency taking action and bringing the concerns of home video content to the attention of the public. When Nightmare was released with a running time sixty seconds longer than that approved of by the BBFC, the film’s distributor, David Hamilton Grant, was sentenced to eighteen months in prison, eventually released after serving six.

Nightmare boasted an impressive list of crew members who would later work on various successful projects, not only in horror but other genres as well. The two editors on the picture, Robert T. Megginson and Jim Markovic, would progress to other duties, with the former penning the eighties thriller F/X: Murder by Illusion whilst the latter would direct the as-yet-unreleased Sleepaway Camp: The Survivor. Their assistant, who was hired after only a couple of weeks due to poor time keeping, was future filmmaker Joel Coen, who had also worked on The Evil Dead and would one day be one half of the respected duo Coen Brothers. Production manager Carl Clifford would later find success with Apollo 13 and Armageddon. The special effects were performed by a selection of talented artists, including Ed French who would work briefly on the New York sequence, under the watchful eye of Lester Loraine, who would sadly take his own life shortly after completing the movie. Who was actual responsible for the designing of the gruesome effects has been a major issue over the years, resulting in legal threats, bitter feuds and a neverending dispute between the director and one of the most popular makeup artists of the era.

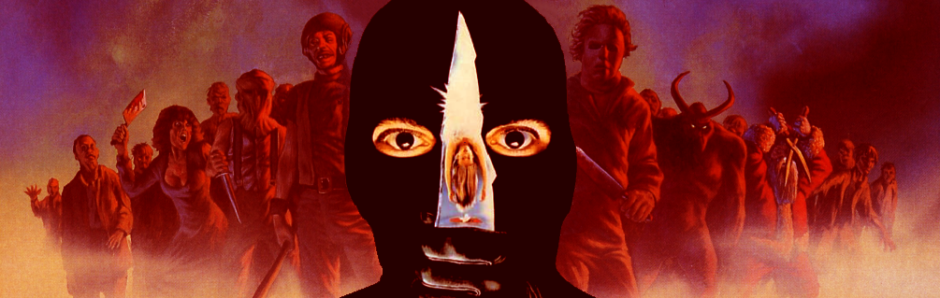

By 1981, Tom Savini had become the man of choice when filmmakers wanted their characters decapitated, disembowelled or mutilated in any hideous way. Having first found fame through his collaborations with fellow Pittsburgh native George A. Romero on the splatter classics Martin and Dawn of the Dead before moving onto some of the most successful slashers of the early eighties, including Friday the 13th, Maniac and The Burning. When Nightmare was released, a caption in the opening credits proudly declared ‘Makeup by Tom Savini,’ indicating that he had been instrumental in designing and creating the gore set pieces that were littered throughout the movie. But upon discovering his name had been added to the poster (declaring ‘From the man who terrified you in Dawn of the Dead and Friday the 13th‘), Savini threatened to sue the filmmakers, eventually resulting in a black box being placed over his name. In fact, Savini expresses nothing but disgust and hatred for Nightmare, stating that he had nothing to do with ‘that piece of shit.’

Despite his insistence that he had no involvement with the film, there is photographic evidence placing him on the set, instructing actor Scott Praetorius (who would portray George as a young boy, slaughtering his mother) on how to wield an axe. When confronted with this, Savini states that he was present as a consultant and nothing more. Scavolini’s response was that of sheer disbelief and frustration, claiming that the effects artist was very hands-on, even pumping the blood when the mother’s dead was chopped off. Part of Savini’s anger was in the fact that it was himself, and not his close friend Loraine, who received credit for the makeup, claiming that the filmmakers had attempted to capitalise on his name. Despite Savini denying to this day that he did officially work on the project, Scavolini’s website includes the caption ‘Special Effects Director: Tom Savini.’ Regardless of who performed which duties, Nightmare has gained a loyal following over the years and stands as one of the slasher’s most intriguing, if flawed, efforts.

4 Responses to The Making Of Nightmare in a Damaged Brain (1981)