Director: Tobe Hooper

Writer: Tobe Hooper, Kim Henkel

Starring: Marilyn Burns, Allen Danzinger, Paul A. Partain, William Vail

Rating: R (USA), 18 (UK), R (Australia)

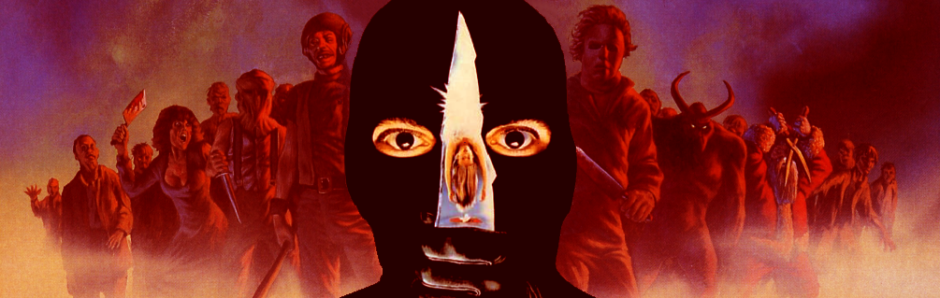

Whilst Psycho may have shocked the genre to its foundation by placing an all-American face on its monsters, very few filmmakers would attempt to expand the concept until one low budget feature arrived fourteen years later by the name of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Every word in its title – ‘Texas,’ ‘Chainsaw‘ and ‘Massacre‘ – conveyed some sense of fear and dread in its audience, even before anything was revealed about the movie itself. It would tap into various themes that were tearing apart the country, such as the brutality of the Vietnam War and the impending oil crisis, and mould them into a simple-yet-effective tale of everyday youths becoming lost on the back roads and falling victim to mutilation and cannibalism.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was the first commercial feature from Austin native Tobe Hooper, a former college professor who had spent a large part of the 1960’s making short films, documentaries and commercials. In 1969 he began work on Eggshells, a psychedelic hippie trip that cost around $50,000 but proved too arty to gain mass appeal. Having developed a love of cinema at an early age (after being given an 8mm camera from his father when he was nine years old), Hooper had spent his youth honing his craft and desperately wanted to make a motion picture, and by the time Eggshells came around he had directed around sixty different short pieces. He had spent a few years as a professor at the University of Austin as he made the film and soon began to toy with the idea of directing a movie. Whilst Christmas shopping in a crowded Montgomery Ward’s store, Hooper became frustrated and claustrophobic at not being able to move and soon started fantasising about the chainsaws that were on show nearby. When he eventually managed to fight his way outside, the idea for a horror script was formed immediately.

Both Hooper and his co-writer Kim Henkel (whom he had collaborated with on Eggshells) have stated various sources that inspired their story. The most well known of these was Ed Gein, a notorious cannibal and necrophiliac from Wisconsin who was arrested in 1957 (just twenty miles from some of Hooper’s relatives) when police found lampshades made from human skin and bowls carved from skulls. Another vivid image that would stay with him over the years was a story that the family doctor once told him when he was seven about his time as a pre-med student, where he skinned a cadaver’s face and wore it to a Halloween party. Clearly an attempt to scare a young child but this was obviously successful. Hooper has also cited the old EC comics, which were notorious for their graphic imagery and were constant victims of moral backlash, eventually becoming the subject of the controversial book Seduction of the Innocent by a German/American psychiatrist, Fredric Wertham.

Henkel has also referenced another true crime that had played a part in influencing their script. Dean Corll was responsible for the death of twenty-seven boys in Houston, Texas in the early ’70’s, eventually being shot dead by one of his young accomplices, seventeen-year old Elmer Wayne Henley. Their victims had been aged between thirteen and twenty and had been lured by fifteen-year old David Brooks to Corll’s home, eventually bringing along Henley, who they had originally intended as a victim. After assisting in various murders, events finally came to an end when Corll turned on Henley and ordered him to rape one of his friends, resulting in Corll being shot. This story made the headlines when his body – and thus, his crimes – were discovered.

A major player in the funding of Hooper and Henkel’s screenplay, then titled Headcheese, was Warren Skaaren, a twenty-five year old Rice University graduate who had landed a job working for the Texas Governor, Preston Smith. Recently, New Mexico had established the Film Commission and had already generated millions of dollars, prompting Smith’s press secretary Jerry Hall and his friend, Bill Parsley, to suggest that Skaaren approach Smith with a similar proposition. Impressed with the idea, Smith agreed and in May 1971 the Texas Film Commission was formed, with Skaaren as its first Executive Producer. Henkel’s friend, Ron Bozman, had been classmates with Skaaren at university and the two were introduced, who would then take Henkel to meet Parsley, who was the Vice President of Student Affairs at Texas Tech University in Lubbock. Next they met up with Robert Kuhn with the intention of forming a corporation, with Hooper and Henkel setting up Vortex while Parsley created MAB, Inc. Kuhn then invested $9,000 of the required $60,000 budget.

The cast that would make up The Texas Chainsaw Massacre consisted of local talent, some of whom had worked with Hooper before. Twenty-three year old Marilyn Burns had been on the film commission board at the University of Texas and had performed in various plays, whilst Teri McMinn had worked with the Dallas Theater Center. For his role as the monstrous Leatherface, Icelandic actor Gunnar Hansen visited a school for the mentally challenged in an effort to portray the character as abnormal. The rest of the cast included Allen (Eggshells) Danziger, William Vail (who would later reteam with Hooper on his commercial breakthrough Poltergeist almost a decade later) and Edwin Neal, who would give a menacing performance as The Hitchhiker.

Principal photography commenced on July 15, 1973 and would last a little over four weeks, in Austin, Bastrop and Round Rock. The conditions were unbearable, with the temperature on the twelfth day reaching an intense 97°F. The crew were forced to shoot between twelve and sixteen hours a day, seven days a week, in order to keep the budget to a minimum, and when one actor (John Dugan, who played Grandfather) insisted that he would only wear the prosthetics once due to the extreme heat, the production was forced to film all of his scenes in one day, resulting in an exhaustive thirty-six hour shoot. Hansen was forced to wear the same clothes everyday without being washed as the filmmakers were worried his overalls would lose colour and by the end of filming Burns’ trousers were so covered in fake blood that they had become solid. The production design for the farmhouse during the last act required various decayed body parts (in keeping with the Ed Gein influence), so makeup artist Dorothy Pearl (wife of DP Daniel Pearl) was forced to gather carcases from from a veterinarian where she worked, while stuntwoman Mary Church collected cow skeletons from her family’s farm. Due to the heat reaching such heights, and mixed with the rotten parts, the smell in the house became unbearable, turning most people’s stomachs. In fact, Burns claimed that immediately after the movie she became a vegetarian.

At Skaaren’s suggestion, the script’s name was changed from Headcheese (at one point being called Leatherface) to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and then the producers set about approaching distribution companies. After almost a year of rejections, they finally signed a deal with Bryanston Distributing Company, who released it theatrically on October 1, 1974, after various problems with the MPAA (Hooper had initially wanted it to be certified a PG as he felt that the film was more amusing than disturbing). The posters claimed that the film was based on true events, which helped to fuel controversy, but it soon fell foul in countries such as the UK and Australia, where it was banned for many years (in fact, it was not released in Britain until 1999, when the BBFC‘s long-standing director James Ferman stepped down). The Texas Chainsaw Massacre would go on to make a staggering $30.8 during its theatrical run and would even be selected for the 1975 Cannes Film Festival. Thirty-five years on and its legacy is still running strong, with the movie constantly coming in the top five on most horror polls and continuing to influence generations of filmmakers.

Pingback: Original vs. Remake: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) | Catie Rhodes