As the sixties came to a close, it seemed that Mario Bava’s winning streak was coming to an end. Whilst the decade had begun with the hugely successful gothic chiller La maschera del demonio (aka Black Sunday), as the seventies drew closer he had produced one commercial failure after another. Danger: Diabolik had gained cult appeal but his subsequent efforts, 5 bambole per la luna d’agosto (Five Dolls for an August Moon) and Il rosso segno della follia (Hatchet for the Honeymoon), had been critically mauled and met with disappointment from his loyal fanbase. Bava was desperate for a hit and was facing issues with taxes which would force him to direct another picture as soon as possible. In 1968, after winning the Volpi Cup at the Venice Film Festival for her turn in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema, popular Italian actress Laura Betti suddenly decided to contact Bava, demanding to know when the two would be able to collaborate together. They immediately set about work on Il rosso segno della follia (literally translated as The Red Mark of Madness), and once the movie had wrapped they began discussing future projects.

Their initial idea was entitled Odore di carne (The Stench of Flesh), a tale of a Los Angeles college besieged by a group of cannibals. Eventually, the concept fell through but both Bava and Betti were determined to work together once again. Their chance came from an unlikely source, cult producer Dino De Laurentiis, who would introduce the director to screenwriter Dardano Sacchetti, whose recent experience with filmmaker Dario Argento on his sophomore effort Il gatto a nove code (The Cat O’ Nine Tails) had resulted in him losing screen credit at the insistence of both the director and its producer, Dario’s father, Salvatore Argento. De Laurentiis had expressed interest in developing his own giallo thriller and so agreed to finance the project. Inspired by And Then There Were None, a 1939 detective novel by mystery writer Agatha Christie, Bava and Sacchetti drafted a story that would follow a similar pattern of a succession of brutal murders at an island mansion. The first draft was penned under the name That Will Teach Them to be Bad, which was also to have been the final line in the script, uttered by one of the children after shooting their parents.

During the early seventies, Sacchetti had developed a creative partnership with fellow writer Franco Barberi but unfortunately this proved to be one of the few people that Bava was unable to collaborate with. When Sacchetti refused to move forward without his friend’s involvement, he eventually backed out of the project and forfeited credit on the shooting script. With The Cat O’ Nine Tails failing to attract the attention of Argento’s first feature, L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird With the Crystal Plumage), De Laurentiis decided to withdraw and Bava was forced to desperately search for an investor, eventually making the acquaintance of Giuseppe Zaccariello, whose previous credits included the cult favourite Femina ridens (The Frightened Woman). Zaccariello was already committed to another project, La grande scrofa nera, and suggested that its writer/director, Filippo Ottoni, take a pass at the screenplay. Ottoni was not very enthusiastic about the story, or the horror genre in general, but in an effort to keep a healthy relationship with his producer he agreed.

Once Ottoni’s draft was completed, Bava decided to revisit his original treatment that he had developed with Sacchetti to find a suitable climax for the story. This would include two children who, in a moment of innocence which results in tragedy, accidentally shooting their mother and father with a rifle, believing their parents to be playing dead. He also amended the daughter’s final line from “That will teach them to be bad” to “Gee, they’re good at playing dead, aren’t they?” The story focused on a beautiful lakeside mansion which suddenly comes up for grabs when its owner is brutally murdered by her husband, who in turn then is dispatched by an unseen assailant. When the news of her passing is announced, an assortment of despicable and dubious types converge on the island with the intention of getting their greedy hands on the luxurious property. But, one-by-one, each of the potential successors are hacked to pieces in a variety of gruesome ways by their competitors, before falling victim themselves.

One thing about Italian horror worth noting is that many of the actors moved in the same circles, so Bava’s film is full of familiar faces from other genre pictures. Claudine Auger, whose character is revealed to be the daughter of the recently deceased, was a former Miss France before finding fame as a Bond girl in 1965’s Thunderball. Her horror work also included the cult flick La tarantola dal ventre nero (Black Belly of the Tarantula), made shortly before Bava’s film. Luigi Pistilli had appeared in the spaghetti westerns Per qualche dollaro in più (For a Few Dollars More) and Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) alongside Clint Eastwood, whilst Leopoldo Trieste would later find minor acclaim with roles in Don’t Look Now and The Godfather: Part II. It is worth noting a considerable number of the actors involved in this movie are now deceased. Leopoldo Trieste, who portrayed the insect-obsessed Paolo, passed away from a cardiac arrest in Rome on January 25 2003 at the age of eighty-five, whilst Betti had suffered a heart attack after surgery the following year at seventy-seven. Two cast members would commit suicide, Pistilli and Claudio Camaso, who took his own life whilst in prison awaiting trial in 1977 after killing a friend during a fight. Other cast members who are no longer with us are Chris Avram (who played the estate agent, Frank Ventura), screen legend Isa Miranda (who portrayed the murdered owner of the bay) and Giovanni Nuvoletti (as her husband and killer).

Shooting commenced on January 18 1971 under the new title Cosi imparano a fare i cattivi (Thus Do We Live To Be Evil). Principal photography took place at a villa owned by Zaccariello in the coastal town of Sabaudia, located on the east side of the country in between Rome and Naples. During the shoot, the name was changed once again to Reazione a catena (Chain Reaction), a reference to the ripple effect that each murder causes on the other characters. To help market the movie internationally, the film was shot in two languages, Italian and English, with each actor performing their dialogue in both, despite most only being fluent in their native tongue. The script was translated by Gene Luotto, a renowned dubbing director, although some of the dialogue would not be translated word-for-word. The interiors of the mansion were shot at Elios Film Studios in Rome, whilst the opening murder was filmed at Villa Frascati in the wine country just outside of the city, which had also been a location used in Bava’s previous features Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace) and Operazione paura (Kill, Baby, Kill).

Reazione a catena would mark the first time that Bava would be credited as his own cinematographer since La ragazza che sapeva troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much) in 1963. Despite his enthusiasm for the project, Bava’s was restrained by a minuscule budget, forcing the director to have to come up with inventive methods during filming. The location in which the movie was shot contained very few trees, yet the script required a heavily wooded area, so Bava had members of the crew crouching just out of frame with branches that they would hold up to give the illusion of a forest. Unfortunately, this trick would seem so ridiculous that many of the cast members were unable to keep a straight face whilst shooting. Utilising the method he had used on Blood and Black Lace, for tracking shots the director would push the camera across the ground mounted to a child’s wagon. Filming finally came to an end on February 28 and was immediately rushed into post-production under the watchful eye of editor Carlo Reali, who would work with Bava the following year on the gothic chiller Gli orrori del castello di Norimberga (Baron Blood).

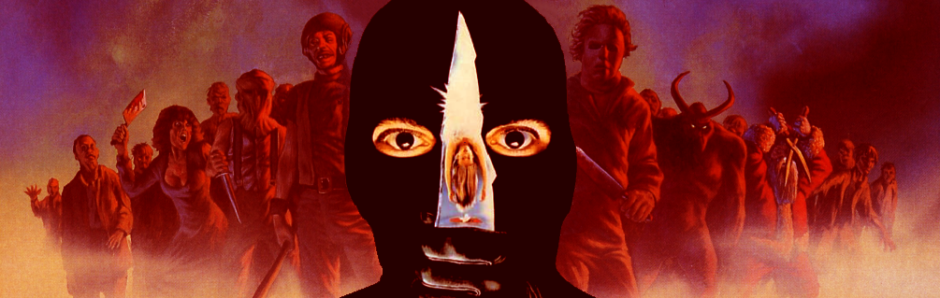

When released in Italy on September 8 1971, Reazione a catena was a financial disappointment for both its distributors and director. During its screening at the 1971 Avoriaz Film Festival, horror legend Christopher Lee (who had previously worked with Bava on La frusta e il corpo (The Whip and the Body) in 1963) was disgusted by what he saw on screen and disappointed with his former collaborator’s tasteless flick. The following year, the movie was acquired by fledging distribution company Hallmark Releasing Corporation and released under the title Carnage, often screened on a double bill with Wes Craven’s rape/revenge drama The Last House on the Left. In fact, at one point Reazione a catena was even renamed The Last House on the Left Part 2, despite being shot six months before Craven’s feature. Another, more famous, title used was Twitch of the Death Nerve, which the film is still often referred to as. Under the name Bay of Blood, the movie was included on the UK’s ‘video nasty’ list and subsequently banned during the eighties. Since then, it has been re-evaluated and is now considered a major influence on the slasher genre, most notably such rural efforts as Friday the 13th, The Burning and Sleepaway Camp.

One Response to SPAGHETTI SLASHERS – Twitch of the Death Nerve