Italian horror has always been a little derivative. I vampiri (also known as The Devil’s Commandment) reflected the gothic sensibilities of Hammer, that were enjoying their most prolific period at the time of its release. Even more explicitly, Lucio Fulci capitalised on the success of Dawn of the Dead (released in Italy as Zombi) be creating his own onslaught of the undead and titling it Zombi 2, in an attempt to fool audiences into believing they were in fact watching a legitimate sequel. When Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left made a killing at the box office, countless independent filmmakers immediately jumped on the rape/revenge bandwagon and attempted to produce their own spin on the formula. In America, the results were mixed, with the ultra sleaze of Meir Zarchi’s I Spit on Your Grave and Abel Ferrara’s Ms. 45 competing with such Italian offerings as Pasquale Festa Campanile’s Autostop rosso sangue (aka Hitch Hike) and Ruggero Deodato’s La casa sperduta nel parco (The House on the Edge of the Park), the latter of which co-starred The Last House on the Left‘s David Hess in equally despicable roles.

Perhaps the most underrated of this cycle was Aldo Lado’s L’ultimo treno della notte which, like most Italian films, would be released under a variety of titles over the years including The New House on the Left, Xmas Massacre and, most famously, Night Train Murders. Lado’s movie, which followed the same template as Craven’s story (itself a blatant steal of Ingmar Bergman’s Oscar winner Jungfrukällan, aka The Virgin Spring) was a more professional and polished affair, which utilised its claustrophobic setting to immediately isolate its protagonists and offer them no hope of escape. But whereas The Last House on the Left‘s central villain was the menacing Krug (Hess), a sexual deviant recently escaped from prison, Night Train Murders‘ chief antagonist is a middle-aged, respectable woman, a far cry from the kind of rapist one would normally expect to see in this kind of feature. Despite it being two young criminals who actually violate the girls, they are merely pawns in a sick and twisted game that the woman is playing, which eventually results in the death of two innocent teenagers.

Lado was born in Fiume, Italy, on December 5 1934. He took his first step into filmmaking as an assistant director on the 1967 western La più grande rapina del west (The Greatest Robbery in the West), before making his own official debut four years later with La corta notte delle bambole di vetro (Short Night of the Glass Dolls), a low budget giallo which followed the standard formula of a tourist investigating a crime, in this case the disappearance of his girlfriend. His follow up, Chi l’ha vista morire? (Who Saw Her Die?), showed Lado experimenting with the genre even further, slowly developing the talents that he would later put to use in Night Train Murders. Whilst the bloodshed and nudity is minimal, it is the power of suggestion that the director employed which helped develop an air of menace and tragedy as the girls and humiliated, raped and eventually murdered. Despite a lack of gore, the movie still fell foul of the ‘video nasty’ which hunt in Britain in the mid-1980’s, which would result in a selection of European pictures (predominantly Italian, and most notably by notorious filmmakers Lucio Fulci, Joe D’Amato and Deodato) being banned for the next twenty years.

L’ultimo treno della notte was first brought to Lado’s attention by Roberto Infascelli, his producer friend who had seen The Last House on the Left and wanted to make something similar. Despite Lado not being familiar with the film himself, the premise intrigued him and he agreed to direct, developing Infascelli’s treatment (which he had conceived with Ettore Sanzò, previously responsible for La polizia chiede aiuto, aka What Have They Done to Your Daughters?) into a screenplay along with Renato Izzo, of La muerte llama a las 10 (The Killer Wore Gloves) fame. Lado began collecting together a talented crew which consisted of cinematographer Gábor Pogány, who had lensed the cult concert Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii, production designer Franco Bottari (Svegliati e uccidi, aka Wake Up and Die) and editor Alberto Gallitti (Se tutte le donne del mondo, aka Kiss the Girls and Make Them Die). With Dario Argento being a major draw in Italy at that time, the producer decided to recruit the services of the legendary Ennio Morricone to compose the atmospheric score. Morricone had not only worked on Argento’s first three movies (L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo, Il gatto a nove code and 4 mosche di velluto grigio) but also Fulci’s Una lucertola con la pelle di donna (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin) and Tonino Valerii’s Mio caro assassino (My Dear Killer).

Fans of Argento’s earlier output will also recognise various actors that populate the eponymous train. One of the rapists was played by Flavio Bucci who, two years later, would be savagely attacked by his own dog in Suspiria. The role of his on screen friend went to Gianfranco De Grassi, who would later appear in the Argento-produced 1989 horror La chiesa (The Church). The instigator, credited simply as the ‘Woman on the train,’ who prompts the thugs to rape the girls, was portrayed with a menacing glee by Moroccan actress Macha Méril, more famous to horror fans as the psychic Helga Ulmann, the first victim in Profondo rosso (Deep Red). Enrico Maria Salerno, who would play the father of one of the victims (who, just like in The Last House on the Left,would exact bloody revenge on the thugs), had appeared in Argento’s 1970 debut, The Bird With the Crystal Plumage, as Inspector Morosini. Irene Miracle, who would portray one of the young victims of the piece, would later appear in the opening sequence of Argento’s Inferno, although sadly her co-star, the beautiful Laura D’Angelo, would scarcely act afterwards. For lovers of Massimo Dallamano’s What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, there are also appearances from Marina Berti (as D’Angelo’s mother) and Franco Fabrizi.

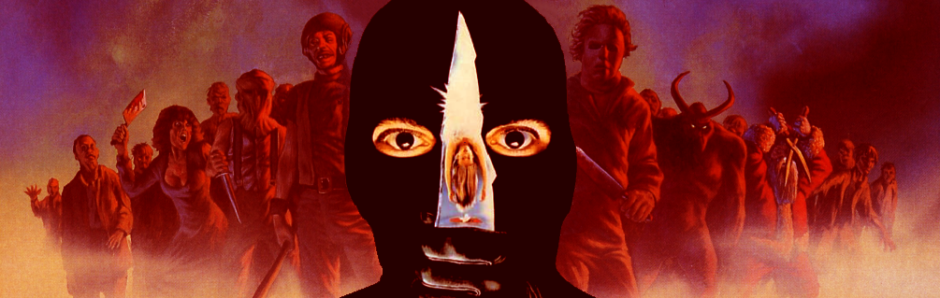

Night Train Murders opens in Germany with the senseless mugging of an alcoholic Santa Claus by two hoodlums, Blackie and Curly (Bucci and De Grassi, respectively), who then make their way to the nearby station and board a train. Two pretty young teens, Margaret and Lisa (Miracle and D’Angelo), are heading to Italy to visit Lisa’s family for Christmas, when the come across the crooks who are attempting to hide from the conductor due to their lack of tickets. Blackie launches himself at an uptight-looking woman (Méril), who suddenly seems to enjoy the attention, much to his surprise. The train comes to a halt and so Margaret and Lisa change onto a near-empty one, hoping to get home before it gets too late. But soon Blackie and Curly, a hopeless drug addict (much like The Last House on the Left‘s Junior, break into the girl’s compartment and, along with the woman, begin to taunt and scare them, with their deeds eventually turning sexual. In perhaps the movie’s most horific moment, Lisa is forced to remove her underwear and spread her legs, whilst the trio admire her body, only for one of them to plunge a switchblade into her vagina after declaring it to be ‘as tight as a frightened arsehole.’ Lisa’s mutilated corpse is thrown from the train and they immediately turn their attention to Margaret, dragging a voyeuristic elderly passenger into the room and forcing him to rape her. In a moment of panic, she runs from the compartment and jumps out of the window, her body crashing lifelessly against the rocks below.

Lisa’s parents await at the station for their arrival and grow concerned when they are not on the train, although the conductor does inform them that many passengers changed trains earlier on so they should be arriving later that night. The three killers exit the train (with Blackie and Curly using the girl’s tickets) and Lisa’s father, a doctor (another The Last House on the Left connection), nurses the woman’s leg before inviting them back to his home. His wife recognises a scarf that one of them is wearing, as it fits the description that Lisa had given over the phone when describing her latest purchase, but the father dismisses it as coincidence until the news of his daughter’s death is announced on the radio. In a fit of rage, he hunts both of the young men down and executes them, although the woman manages to convince him that she had played no part in the incident and had in fact tried to stop them.

There is a subtle social commentary at play in between the moments of sexual abuse and murder. The fact that the father believes the woman, who had been the most to blame, just because she was middle class and elegant, showed the prejudice that society has against the young and how people immediately fall into a stereotype – young thug, respectable lady. It is also worth noting how the more superior character (class-wise, at least) plays upon the criminals’ lack of sophistication and intelligence for her own entertainment. Each scene is accompanied by an eerie score by Morricone, who once again utilises his C’era una volta il West (Once Upon a Time in the West) gag of having one of the characters playing a harmonica which adds to the tension of any given scene. The opening and end credits to the movie feature a track entitled A Flower’s All You Need by Greek singer Demis Roussos. Filmed across three countries (Innsbruck, Austria, Munich, Germany and Verona, Italy), the majority of the action takes place on-board the train and this is the perfect setting for such an intimidating premise. Sadly, the movie was banned in the United Kingdom and received a limited release in most other countries, reducing it to a cult curiosity. Coincidentally, Aldo Lado received a ‘Special Thanks’ credit for Eli Roth’s 2007 Euro-horror Hostel: Part II, perhaps as his train sequences were clearly inspired by this movie.

3 Responses to SPAGHETTI SLASHERS – Night Train Murders