2009 celebrates thirty years since the release of Zombi 2, the movie that would not only cause controversy around the world but would also launch its creator to both great acclaim and notoriety. But there was more to Lucio Fulci than just excessive gore at the hands of the living dead, for the Italian filmmaker had flirted with every conceivable genre throughout his forty-year career; from giallo and comedy to westerns and musicals. Yet it was his reputation as the godfather of gore and his use of surreal and brutal imagery that had caused him to become one of the most adored yet misunderstood filmmakers to emerge from the Italian horror industry. Often described as both a misogynist and plagiarist, Fulci has perhaps divided audiences and critics more than any other filmmaker during the seventies and eighties, resulting in three of his movies from that era being blacklisted in the United Kingdom as ‘video nasties.’ Now, thirteen years after his death, horror fans have been able to discover much of the lost and outlawed material that censors the world over had deemed unsuitable, with DVDs providing re-mastered and uncut prints of some of his most beloved and notorious work.

Italian horror cinema has often been ridiculed for its lack of plausibility, nonsensical structure and extreme violence. Another common criticism was in the way that some of its filmmakers would shamelessly duplicate many successful American movies and, in some cases, even pass themselves off as legitimate sequels. Perhaps the most popular of this type of film was Zombi 2, which had been marketed as a follow-up to George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, a movie that had been a huge success in Europe under the alterative title Zombi the previous year. Both the Italian zombie features of the late seventies (which had themselves been influenced by the mondo and cannibalism films of the last two decades) and the giallo thrillers were often accused of being misogynistic due to the extreme violence that was levelled at their female victims. Even more so than many of his contemporaries (such as Dario Argento, Sergio Martino and Umberto Lenzi), Fulci would come underfire for the treatment of women in his movies, with the British government going so far as to ordering for all copies of his 1982 giallo slasher Lo squartatore di New York (The New York Ripper) to be removed from the country.

Fulci was born on June 17 1927 in Rome and was brought up in a Catholic household. Having briefly studied medicine, he would eventually become an art critic before attending Luchino Visconti’s Experimental Film Centre, where he would be schooled by the likes of Umberto Barbaro, Luigi Chiarini and Francesco Maselli. In order to be accepted, Fulci was required to pass an oral exam, in which Visconti himself would challenge him on various aspects of the film industry. One question in particular was with regards to Visconti’s own 1943 feature Ossessione (Obsession), in which Fulci had replied that his film had stolen from Renoir. Suitably impressed with the young man’s honesty, Visconti had personally accepted him onto the course. He began his career as a writer with the 1948 documentary Pittori Italiano dei dopoguerra, before working as a second assistant director for Marcel L’Herbier on his biblical feature Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei (Last Days of Pompeii). During this era he would work for such renowned filmmakers as Federico Fellini, Roberto Rossellini and Mario Bava.

Soon afterwards, Fulci would move into the comedy genre, where he would frequently collaborate with Italian legend Toto. In 1959, he would finally make his directorial debut with Il ladri (The Thieves), which would prove to be a commercial failure. Many of his early films would employ the slapstick which had become commonplace for Italian comedies of the era. Fulci had not wanted to direct himself, having previous declined the chance to helm Toto all inferno (Toto Goes to Hell) five years earlier. Soon afterwards, he would score his first success as a director in his own right with the musical Ragazzi del jukebox (Jukebox Kids). Aside from frequent collaborations with Toto, other big names that Fulci would work alongside were pop star Mina, on the 1960 comedy Urlatori alla sbarra (Howlers of the Docks), and Franco French and Ciccio Ingrassia on I Due Della Legione (Two Foreign Legionnaries).

In 1969, Fulci would make his first transition into the thriller genre with Una sull’altra (Perversion Story), an early example of the giallo film. His next effort, Una lucertola con la pelle di donna (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin), would result in the first significant controversy of his career, with Carlo Rambaldi’s realistic special effects resulting in the filmmakers being taken to court under charges of cruelty to animals, forcing Rambaldi to have to present his work before judge and jury to prove that the disemboweled dogs shown in the film were in fact fake. It would be around this time that critics began making comparisons between Fulci and Dario Argento, who himself had also been compared to Mario Bava. With the giallo having become a box office draw with Argento’s own debut L’uccello dale piume di cristallo (The Bird With the Crystal Plumage), Fulci would become one of the most popular directors of the genre during the early seventies, although whereas Argento’s earlier efforts – Il gatto a nove code (The Cat o‘Nine Tails) and 4 mosche di velluto grigio (Four Flies on Grey Velvet) – had gained acclaim for their complex storylines and impressive cinematography, Fulci would earn a reputation as extremely violent and confrontational.

In 1972, he would direct the critically acclaimed Non si sevizia un paperino (Don’t Torture a Ducking), which would begin an obsession with religious figures being responsible for acts of brutal violence – something he would also flirt with in 1980’s Paura nella città dei morti viventi (City of the Living Dead). The story would centre on a small Italian town besieged with the mysterious disappearances of several local children and would contain several controversial scenes, including a woman disrobing in order to try and seduce a young boy and its gruesome ending when the killer (a priest) falls to his death from a cliff, his head being split as it collides with a rock on the way down. His next two projects would be Zanna Bianca (White Fang) and Ritorno di Zanna Bianca (Return of White Fang), before Fulci would dabble with the spaghetti western (a popular Italian genre since Sergio Leone’s acclaimed ‘Dollars’ trilogy in the sixties) with his 1975 flick I Quattro dell’apocalisse (Four of the Apocalypse).

His return to the giallo would come in 1977 with Sette Note in Nero, released in various territories as either Seven Notes in Black or The Psychic. Conceived by Fulci and Roberto Gianviti, the screenplay was met with disappointment from its producers, Luigi and Aurelio de Laurentis, who were unimpressed with the ending. Eventually, frequent collaborator Dardano Sacchetti (who had also worked on the likes of Reazione a catena (Twitch of the Death Nerve) and The Cat o’Nine Tails) would help contribute to the scenes that Fulci would find problematic. Unfort

unately, when Rizzoli decided to distribute the movie they released it during the summer, the least profitable time of year, resulting in the film failing at the box office. Despite this, The Psychic would remain one of the director’s favourite of his own films, alongside Don’t Torture a Duckling.

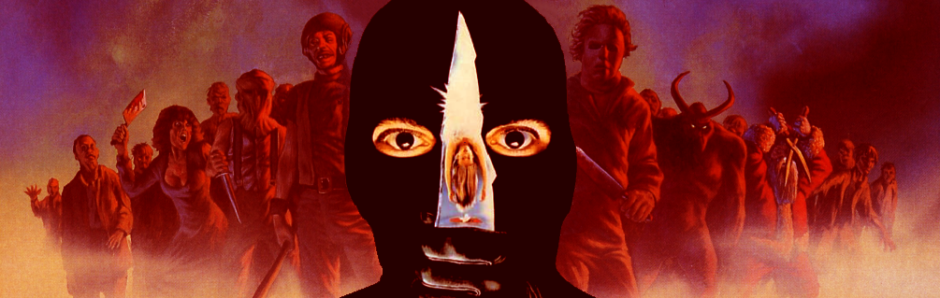

Soon afterwards, Fulci was contacted by producer Fabrizio de Angelis, who had viewed The Psychic and was suitably impressed enough to want to hire the director for his next feature. Wanting to capitalize on the excessive brutality of both the mondo and cannibal movies which Italy had grown notorious for throughout the sixties and seventies, the resulting effort would return the zombie film back to its voodoo roots, forgoing the ‘living dead loose on society’ formula which had become popular since the success of Night of the Living Dead and instead taking the genre back to its Haiti origins. Despite Zombi 2 being titled as such to fool audiences into believing that the film was connected to Dawn of the Dead, the movie would in fact share little with Romero’s classic, with Fulci’s story being far more savage and unnerving. Two scenes in particular would help cement the film’s reputation with horror fans – an underwater fight between a zombie and a shark and, a sequence which would be referenced in much of his later work, a woman’s eyeball being punctured by a splinter as a zombie’s hand had broken through a window. The film would be placed on the Director of Public Prosecutions’ ‘video nasty’ list in the UK under the more interesting moniker Zombie Flesh Eaters.

Zombi 2 had marked the beginning of what would become a prolific collaboration with Gianetto de Rossi, whose special effects would play a substantial role in the film’s success. Unfortunately, de Rossi was unavailable for Fulci’s next zombie flick, the truly disturbing City of the Living Dead, which would mark the start of his unofficial ‘Gates of Hell trilogy.’ In its most notorious scene, scream queen Antonella Interlenghi would vomit out her intestines whilst bleeding through the eyes (the destruction or mutilation of eyes would play a major part of Fulci’s later work). The movie would also feature Giovanni Lombardo Radice, a disturbing character actor who would also appear in other controversial flicks of the era such as Apocalypse domain (Cannibal Apocalypse) and Cannibal Ferox, whose demise in City of the Living Dead would involve a drill being forced through his skull. The trilogy would continue with the equally disturbing E tu vivrai nel terrore – L’aldilà (The Beyond) and Quella villa accanto al cimitero (The House By the Cemetery), both of which would also be labeled video nasties in Britain.

Whilst Romero had made zombies popular once again in America, Fulci’s contributions to the genre would have a profound effect on the Italian industry, prompting various filmmakers to try their hand at producing their own gruesome zombie flick. This would result in an overabundance of similar efforts, including Lenzi’s Incubo sulla citta contaminata (Nightmare City), Bruce Mattei’s Apocalipsis cannibal (Zombie Creeping Flesh), Andrea Bianchi’s Le notti del terrore (Burial Ground) and Claudio Fragasso’s Oltre la morte (Zombie 4). Fulci, meanwhile, would continue to experiment with other subject matters, from the works of Edgar Allen Poe’s Il Gatto nero (The Black Cat) – which had previously been adapted by Roger Corman for Tales of Terror – to perhaps the most controversial work of his entire career, a film that would even alienated much of his core fanbase.

Shot on location in New York City and taking elements from both the giallo and slasher genre, 1982’s The New York Ripper would sacrifice character and plot for scenes of brutal violence against women, most of whom seem to be punished for their errant ways. Several of the murders seem inherently sexual, with the killer’s blade penetrating vaginas and breasts in truly savage fashion. Other, non-violent, sequences include a woman masturbating whilst watching a sex show and another being violated by a man’s toe as his friends look on. One ill-advised aspect of the script was the decision to give the killer a bizarre voice, taking the guise of a duck as he taunts the police with endless phone calls. Whilst some critics have taken it upon themselves to defend Fulci’s previous work, few could justify the extreme nature of The New York Ripper, which proved to be a deeply sleazy and unpleasant affair.

Throughout the eighties, there would be a steady decline in the quality of Fulci’s work, starting with 1983’s Manhattan Baby and continuing with his various adventure flicks, including La Conguista de la Tierra Perdida (Conquest) and I guerrieri dell’anno 2072 (The New Gladiators). In 1987, suffering from hepatitis and becoming increasingly disillusioned with his latest project, Fulci would walk from his sequel Zombi 3 after shooting approximately forty minutes of footage, with the remaining being shot by Bruno Mattei. Fulci would later express his disappointment with the finished product and would subsequently disown the movie. Some saw his 1990 effort Un Gatto nel cervello (Cat in the Brain/Nightmare Concert) as a self-referential statement on the effects that violent art have on not only its viewers but also its creator, although the film would fail to achieve the same level of success as his early eighties offerings. His last movie, Le porte del silenzio (Door to Silence), was released in 1991. Lucio Fulci would pass away due to complications resulting from diabetes in his hometown on March 13 1996. He was sixty-eight years old and had directed over fifty feature films. His legacy has grown since his death and has since become one of the most respected Italian filmmakers of the horror genre. As fans often proclaim, Fulci lives!

Pingback: Karate Kid Soundtrack