Whilst some giallo filmmakers are occasionally revered by critics for their stylish use of cinematography and almost operatic violence, one director who was met with constant cynicism, bewilderment and even hatred was Lucio Fulci. Considered by some to be a pioneer in exploitation, others often dismissed him as a talentless hack, plagiarising the success of more talented artists. Perhaps most known for his gruesome zombie classics City of the Living Dead, The Beyond, The House By the Cemetery and Zombi 2, Fulci had spent the latter half of his career cementing his reputation as the ‘godfather of gore.’ But, a few years before finding international success as a regular on the UK’s ‘video nasty’ list, he had directed three dark and seductive giallo thrillers, 1969’s Una sull’altra (aka Perversion Story), 1971’s Una lucertola con la pelle di donna (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin) and Non si sevizia un paperino (Don’t Torture a Duckling), released the following year. Although they would feature the trademark nihilism and brutality which his fans have come to expect, his gialli were also beautifully constructed and nightmarish experiments in twisted narratives and perverse violence.

Lucio Fulci was born on June 17 1927 in Rome. Having studied medicine, he eventually attended Luchino Visconti’s Experimental Film School under such cinema experts as Luigi Chiarini, Umberto Barbaro and Nanni Loy before taking his first steps into the industry by penning the documentary Pittori Italiano dei dopoguerra in 1948. During his early years as a writer, Fulci would collaborate with a succession of respected filmmakers, finally making his own directorial debut with I ladri (Contraband), a comedy designed as a vehicle for popular Italian actor Totò, in 1959. For the next twenty years, he would experiment with a variety of genres, such as musicals (Urlatori alla sbarra), adventure (I due pericoli pubblici) and western (Tempo di massacro), before moving into darker territories with Perversion Story. His sophomore thriller, A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, gained notoriety due to a scene which featured disembowelled dogs. Convinced that the filmmakers had violated animal regulations, Fulci was taken to court, forcing his special effects artist, Carlo Rambaldi, to present the prop to the judge in an effort to prove that it was all an illusion.

In 1970, the Italian film industry would take a dramatic turn and become obsessed with giallo, a type of thriller that had been inspired by old pulp novels of the thirties. Heralded by Dario Argento’s audacious debut L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage), many filmmakers would suddenly turn to the horror genre and soon the market became flooded with variations of the formula, including Sergio Martino’s Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh (The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh), Aldo Lado’s La corta notte delle bambole di vetro (Short Night of the Glass Dolls) and Giuliano Carnimeo’s Perché quelle strane gocce di sangue sul corpo di Jennifer? (The Case of the Bloody Iris). Fulci had always been one to sense a new fad and would instantly jump onto the bandwagon, and so followed A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin with Don’t Torture a Duckling, which may have utilised such plot points as voodoo dolls and killer priests but would still follow the detective template that had become a standard of the genre since the release of Mario Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace) almost a decade earlier.

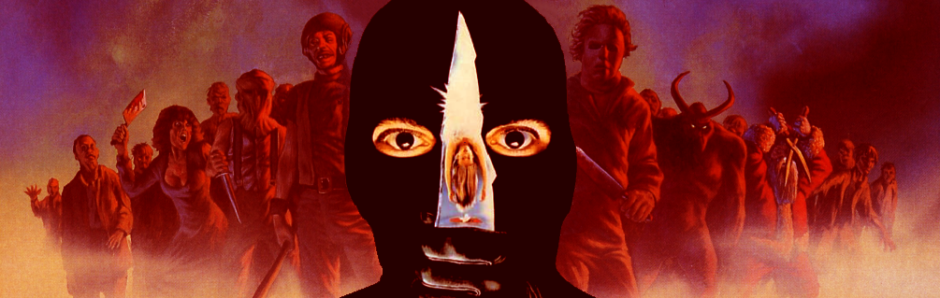

A series of child disappearances in a rural Italian village and soon the local authorities draw up a list of suspects, including a supposed witch and a creepy Peeping Tom, but each time the police think that they have the assailant the real killer strikes again. This concept of one antagonist constantly replacing the last was previously used by Bava in his 1971 Agatha Christie-style thriller Reazione a catena (Twitch of the Death Nerve), although the lack of sympathetic characters makes it difficult to distinguish the hero from the villain. It would not be until 1979’s Zombi 2 that Fulci would become obsessed with images of torn flesh and spilt guts and so Don’t Torture a Duckling would not be as gruesome as his later work, instead focusing on the children who are targeted by the mysterious killer and the investigation that attempts to save them. Less convoluted but equally bizarre than his eighties output, Don’t Torture a Duckling would still be a confrontational and disturbing piece.

This project would mark yet another collaboration between Fulci and his regular screenwriter Roberto Gianviti, whose previous work had included Come rubammo la bomba atomica (How We Stole the Atomic Bomb), Perversion Story and A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, although this time they would be joined by the services of Gianfranco Clerici (Una farfalla con le ali insanguinate/The Bloodstained Butterfly). Fulci would surround himself with talent which he previously worked with, such as cinematographer Sergio D’Offizi (All’onorevole piacciono le donne (Nonostante le apparenze… e purché la nazione non lo sappia)), makeup artist Franco Di Girolamo (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin) and composer Riz Ortolani (Perversion Story),with vocals by popular Italian singer Ornella Vanoni. New additions to the crew included production designer Pierluigi Basile and costume designer Marisa Crimi.

For his cast, Fulci approached several actors who were recognisable faces in their native country. Brazilian star Florinda Bolkan had previously collaborated with the director on A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, as had Tomas Milian and Franco Balducci on Perversion Story. German actress Barbara Bouchet’s prior credits included the thriller La tarantola dal ventre nero (Black Belly of the Tarantula), Irene Papas had appeared in the cult horror Un posto ideale per uccidere (Oasis of Fear) and Georges Wilson had been seen in 1962’s Le diable et les dix commandements (Devil and the Ten Commandments). As with much of Fulci’s later work (and such contemporaries as Bava and Argento), the cast would be made up of performers of various nationalities and so the movie would be dubbed according to the country in which it was being released, as opposed to the traditional method of subtitles. This has often been a criticism levelled at not only Fulci but Italian horror in general, as bad dubbing can sometimes reduce the effect of a movie and leave it seeming ridiculous and unconvincing.

Filming for Don’t Torture a Duckling commenced on May 2 1972 in various rural locations around Italy, including Matera (Basilicata), Monte Gelato Falls (Treja River) and Monte Sant’Angelo (Foggia, Apulia) for approximately one month. The shoot was a relatively enjoyable experience for Fulci who, despite his intense work, was often considered by his peers to be an amusing and pleasant man. One sequence that shocked many fans was the scene in which Bouchet, who had become a sex symbol since her turn as Moneypenny in the 1967 James Bond spoof Casino Royale, would entice a young boy by standing completely naked in front of him and challenging him to go to bed with her. Another controversy that the move would cause would be its portrayal of priests, with the killer eventually revealed to be a man of the cloth. This plot twist angered the Catholic Church (a prominent force in Italy) and the movie was subsequently blacklisted and reduced to a limited release.

Don’t Torture a Duckling made its first public screening on September 29 1972 and gained mostly favourable reviews from the Italian critics, although due to its content it would remain unavailable in the United States for over thirty years. Despite its literal translation of Non si sevizia un paperino being Don’t Torture Donald Duck, the filmmakers wisely avoided a lawsuit from Disney by changing the title to avoid any references to the famous character. Whilst never receiving the kind of cult appeal that his later efforts such as Zombi 2 (which was banned in Britain under the catchier title, Zombie Flesh Eaters) and The Beyond received, Don’t Torture a Duckling remained Fulci’s favourite of his own films and has steadily grown a loyal fanbase over the years, proving to be one of the director’s most underrated films alongside A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin and 1977’s Sette note in nero (The Psychic).