Whilst the likes of Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci have become cult figures in Italian cinema, it is arguable that the country’s greatest export for horror was Mario Bava, an ingenious and stylish filmmaker who, much like Alfred Hitchcock, was a disciplined and intelligent storyteller who would fill his movies with visual metaphors, subtle clues and a dazzling array of beautiful images and breathtaking set pieces. He had redefined gothic horror with his commercial debut La maschera del demonio, known in English-speaking circles as Black Sunday or The Mask of Satan, and had delivered the creepy and nightmarish anthology I tre volti della paura (Black Sabbath), becoming instrumental in bringing Italian horror to worldwide attention. But it was his 1964 effort, Sei donne per l’assassino – more commonly referred to as Blood and Black Lace – which would become his crowning achievement, as it would popularise the giallo format, which would draw heavily not only on crime literature but also the director’s previous picture, La ragazza che sapeva troppo (The Evil Eye/The Girl Who Knew Too Much). But whereas that had been a seductive black and white affair, Blood and Black Lace would be a Technicolor tour de force, a constant assault on the sense that would come to revolutionise the genre.

Filmmaking had always been in his blood. Mario Bava was born on July 31 1914, just one month after the First World War had begun. His father, Eugenio Bava, was a respected cinematographer and special effects artist, having worked on such early cinematic classics as Quo Vadis?, Cabiria and Camicia nera. Both trades are talents which his son would inherit, taking his first step into the industry as a cameraman on Roberto Rossellini’s 1939 short La vispa Teresa (Lively Teresa). Having spelt his childhood on various movie sets, Mario had developed an artistic edge and soon became a cinematographer-for-hire, finally taking his own stab at directing with the 1946 documentary L’orecchio. A decade later, he was hired to lens a horror picture entitled I vampiri but when its director, Riccardo Freda, walked from the project mid-shoot he was forced to complete the film himself. At this time, horror cinema had been outlawed in Italy under the fascist leadership of Benito Mussolini and, after his death in 1945, artistic freedom had slowly begun to allow filmmakers the chance to create more risqué work. After making his official directorial debut in 1960 with Black Sunday, Bava soon become a key figure in the industry and delivering one successful feature after another throughout the sixties.

The project started out as a treatment called L’atelier della morte (roughly translated as The Fashion House of Death) by Black Sabbath‘s co-writer Marcello Fondato. Sensing its potential, Bava decided to expand upon the themes and styles he had explored with The Girl Who Knew Too Much and The Telephone, the first segment of his Black Sabbath anthology, by developing the giallo format. Inspired by the pulp crime novels of the thirties and forties that sported images of women being brutally slain over a yellow sleeve, the giallo would later become Italy’s most profitable and controversial genre, even out grossing the spaghetti western, and this was in no small part due to the impact of Blood and Black Lace. Bava would work alongside Fondato and Giuseppe ‘Joe’ Barilla to develop the story into a complex and violent screenplay. Whereas Black Sunday had sported one shocking set piece – a scene in which suspected witch Asa Vajda (Barbara Steele) has a metal mask with long nails hammered into her face – Blood and Black Lace would boast a succession of shocks that would guarantee the movie notoriety.

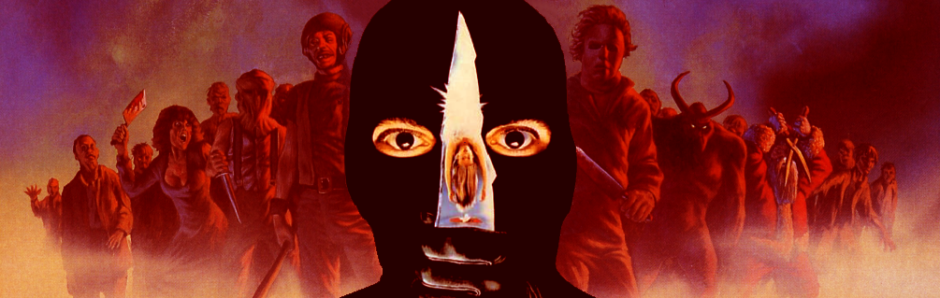

The story centres around the Christian Haute Couture, a fashion empire full of beautiful-yet-shallow models who are being systematically slaughtered by a masked psychotic. Under the watchful eye of house mother Contessa Cristina Como, the young girls seem to enjoy indulging in sin more than gracing the catwalk. But when one of their numbers, Isabella, is hacked to pieces in a nearby park, the authorities call in Inspector Silvester to help solve the case. It seems in this world everyone is a suspect, with each character displaying dubious behaviour and ulterior motives. The plot is full of red herrings, with each of the girls and even Como seeming to display some kind of suspicious mannerism. Events take a turn for the worse when Isabella’s diary is discovered by Nicole, who tries to remove any incriminating evidence of her own devilish deeds. But, one by one, each of the girls is slain in the most graphic manner, with one even having her face pressed against a burning furnace.

With a budget of $150,000, pre-production commenced on what had become Sei donne per l’assassino (Six Women for the Murderer). For the role of Max Marian, the co-owner of the fashion house, Bava approached Cameron Mitchell, an American actor whom he had first made the acquaintance of during the making of Giacomo Gentilomo’s 1961 movie L’ultimo dei Vikinghi (The Last of the Vikings), which Bava had been brought in to help complete the picture. Immediately striking a friendship, the two would start work soon after on Gli invasori (Erik the Conqueror), a loose remake of the Kirk Douglas epic The Vikings. When Blood and Black Lace was being developed, Bava searched for a role for his new friend. In the role of Como was Eva Bartok, a thirty-six year old Hungarian star who had changed her name from Eva Ivanova Szöke in an effort to achieve international success. After spending years in a German concentration camp during the Second World War, Bartok had married a Nazi offer, eventually having her vows annulled to avoid being labelled as a collaborator.

One valuable asset for Bava was in the casting of Mary Arden, an American actress who had started her career as a model and had even graced the front cover of the Italian Vogue, before turning her attention to acting with an uncredited role as a dancer in the 1936 musical King of Burlesque. Due to Blood and Black Lace being a multinational production (primarily Italy and Germany), the cast and crew consisted of various different languages spoken – nine to be precise. To help sell the product in America, it was decided that all of the dialogue would be filmed in English, despite only Arden and Mitchell being fluent in the language (even Bava could only speak Italian), and so a translator was brought in to adapt the script. Unfortunately, the person that they chose was not able to do an exact translation, and so Arden offered to help re-write the dialogue into proper English. This mix of languages was a common practice, with Argento famously employing a similar method with his 1977 supernatural masterpiece Suspiria.

Filming commenced on November 22 1963, with the principal location being the Villa Pamphili, a large house adjacent to a 1.8 km² public park. This would double for the Christian Haute Couture, with some interior sequences shot at A.T.C. Studios, Rome. The shoot would last approximately six weeks, finally wrapping on January 8 1964. This was to be the first full length giallo not to be shot in black and white, with Bava opting to film on Eastman Colour Stock and process in Technicolor. The Italian/West German investors were under the impression that the director had intended to make a routine murder mystery in the tradition of Edgar Wallace, a British crime author who had also been involved in the writing of King Kong in the thirties. But Bava had intended for the film to resemble the old giallo covers, boasting extreme colours and even more extreme violence, predominantly targeted at the female characters. In fact, in many ways Blood and Black Lace, along with Herschell Gordon Lewis’ Blood Feast, could be considered as a forerunner to the body count movies of the eighties. The nihilistic themes of the movie were evident in various shots which saw glamorous mannequin on screen alongside such immoral activities as drug taking, showing the filmmakers’ obsession with the destruction of beauty.

Despite the movie utilising the whodunnit formula, the killer itself was not portrayed by an visible cast member but was in fact Goffredo Unger , one of Italy’s most popular stuntmen who often worked under the alias Freddy Hungar. His later work would include Lucio Fulci’s western I quattro dell’apocalisse (Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse) and the splatter classic Apocalypse domani (Cannibal Apocalypse). Much like with Michael Myers in Halloween, the killer is faceless, instead sporting a blank white mask, although the edition of a Fedora kept the image in keeping with the old murder mystery novels. Due to his lack of funds, Bava was forced to be imaginative with his cinematography (which he performed alongside Black Sunday‘s Ubaldo Terzano. For a shot which required a dolly to travel through a room amongst the models, the director instead mounted the camera on top of a child’s wagon and pushed it along by hand. Similarly, for a crane shot, a simple see-saw was used to raise the camera. Despite American International Pictures initially lined up to distribute the picture, the end result caused them to back out and so instead the US release was handled by Woolner Brothers, an independent distribution company ran by Lawrence and Bernard Woolner. All of the actor’s dialogue was dubbed in Los Angeles by Lou Moss, with each of the male characters performed by Disney voice artist Paul Frees. In both America and Italy, Blood and Black Lace was a critical failure, eventually slipping into obscurity until it resurfaced on home video in 1989. Since then, it has slowly gained the recognition it has so rightfully deserved and is now considered one of the most important movies in Italian cinema.

17 Responses to SPAGHETTI SLASHERS – Blood and Black Lace