It isn’t easy following in the footsteps of a legendary father, and no one knows that more than Lamberto Bava. Having spent his childhood immersed in the industry, it was perhaps inevitable that he would eventually turn to directing himself, although the shadow of Mario Bava would be cast over everything he attempted. Starting out as an assistant to his father, he would later become a protégé of such respected auteurs as Dario Argento, learning from the masters as he searched for his own distinctive style. But his father had been responsible for the sudden interest in Italian horror through such sixties classics as La maschera del demonio (aka Black Sunday), I tre volti della paura (Black Sabbath) and Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace), cementing his reputation as one of the country’s greatest filmmakers, despite the following decade resulting in a slew of critically mauled and misunderstood efforts. But his legacy would become a thorn in the side of many genre directors, who were constantly compared to and expected to emulate both his style and success. And none felt the pressures more than his son.

Lamberto Bava was born on April 3 1944 in Rome, two years before Mario would make his directorial debut with the documentary L’orecchio. His grandfather, Eugenio Bava, had been a pioneer in special effects during the early years of cinema, plying his trade on the classics Quo Vadis? and Cabiria, released in 1912 and 1914, respectively. Being only sixteen when his father directed his first masterpiece, Lamberto would embrace cinema from an early age and, at the age of twenty, became an assistant to Mario on his science fiction horror Terrore nello spazio (Planet of the Vampires). For the next decade, Lamberto would frequently collaborate with his father, eventually being promoted to assistant director on a variety of classics from Operazione paura (Kill Baby, Kill) and Il rosso segno della follia (Hatchet for the Honeymoon) to Reazione a catena (Twitch of the Death Nerve) and Cani arrabbiati (Kidnapped/Rabid Dogs), the latter of which would remain unreleased for many years after the produce passed away and all of his assets were seized by the courts. When Mario became to ill to complete his work on Shock in 1977 (which would prove to be his swan song), Lamberto stepped in, before collaborating with other respected filmmakers such as Argento (on Inferno, which Mario would also provide matte paintings for) and Ruggero Deodato.

In 1980, Lamberto made his own directorial debut with Macabro (more commonly known as Macabre), which told of a tormented and deranged woman who is released from an asylum and returns to the old meeting ground where she conducted her affair to continue her relationship with her dead lover. The project had been conceived by Pupi Avati, who had previously penned the cult horror La casa dalle finestre che ridono (The House With Laughing Windows), and based on a true incident that occurred in New Orleans in 1977. Co-scripted by Bava with Antonio Avati and Roberto Gandus, the movie was greeted with mixed reviews and a lukewarm reception. Sadly, soon afterwards, Mario Bava passed away from a heart attack and Lamberto would remain hidden until teaming up once again with Argento on his 1982 slasher Tenebrae. The following year, he would return to the director’s chair with his acclaimed giallo thriller La casa con la scala nel buio, literally translated as The House of the Dark Stairway.

La casa con la scala nel buio was to be a four-part miniseries for Italian television which would run at approximately a half hour and each end with a violent cliffhanger. Having worked alongside his father on an array of murder mysteries, Bava was confident that he could do the concept justice and a script was written, by husband and wife team Dardano Sacchetti and Elisa Briganti. Sacchetti had enjoyed a prolific film career since his first screenplay, Il gatto a nove code (The Cat O’ Nine Tails), was filmed by Argento in 1971. Other successes would follow, such as Twitch of the Death Nerve, Apocalypse domani (Cannibal Apocalypse), before collaborating on several Lucio Fulci movies with Briganti several, including Zombi 2 and Quella villa accanto al cimitero (The House by the Cemetery). The script would feature various elements from previous giallo features before, such as a successful musician as the protagonist (as with Profondo rosso/Deep Red) and a creepy voice caught on tape (Il gatto dagli occhi di giada/Watch Me When I Kill), whilst the final reveal had echoes of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.

The movie opened with a sequence which would not have been out-of-place in Bava’s 1985 horror comedy Dèmoni (Demons), in which three children creep into an old haunted building and one is dared to fetch a ball from down in darkened cellar. The boy eventually caves into peer pressure and heads down the stairs, only to be followed by screams and the bloodied ball flying out at them moments later. It is soon revealed that this was in fact a scene from the latest horror film to be scored by Bruno, a young and popular composer who has recently moved into an isolated villa owned by the charming Tony Rendina to focus on his work. With this marking his first move into thriller territory, he is a little apprehensive about what is to be expected of him but its director, Sandra, has faith that he will succeed. But on his first night, as he attempts to record a sample for his landlord, he hears a bizarre voice in the recording which sparks a chain of events that leads to murder and mystery.

Bava immediately began casting for his feature, approaching twenty-five year old Andrea Occhipinti for the role of Bruno, with Sacchetti having already worked with him before on Lo squartatore di New York (New York Ripper). Perhaps the most intriguing casting choice was for that of Tony Rendina, which would be offered to Bava’s assistant director, Michele Soavi, who would later enjoy a directing career of his own with such cult favourites as Il mondo dell’orrore di Dario Argento (Dario Argento’s World of Horror) and La chiesa (The Church). Bava would also surround himself with a selection of talented crew members. Cinematographer Gianlorenzo Battaglia had already worked on the underwater sequences that had opened Inferno, as well as assisting Mario Bava on 5 bambole per la luna d’agosto (Five Dolls for an August Moon), Hatchet for the Honeymoon and Twitch of the Death Nerve. Giovanni Corridori was the most in-demand special effects artist in Italy at that time, having producing groundbreaking makeup on Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns, The House with Laughing Windows, Zombi 2 and Tenebae.

Filming would take place for three weeks in Rome at a villa owned by one of the producers. Shot on 16mm, the film would eventually be blown up to 35mm when the network decided that the result would be too violent for television and would instead be distributed as a movie. Trimmed from its original running length of 108 minutes (which would have been split into four parts) to 96 minutes, the feature would instead be released theatrically. Bava used this project to hone his craft, utilising its one location to generate claustrophobia and an immediate sense of dread, keeping the characters to a minimum (there are only seven principals) and instead focusing on the protagonist’s paranoia. Each scene would be heightened by the creepy score, often used during scenes in which Bruno is attempting to compose music on his piano. The score was created by brothers Guido and Maurizio de Angelis, former employees of RCA Italiana and acclaimed musicians, responsible for the compositions for I corpi presentano tracce di violenza carnale (Torso), La montagna del dio cannibale (The Mountain of the Cannibal God) and Sensitività (The House by the Edge of the Lake).

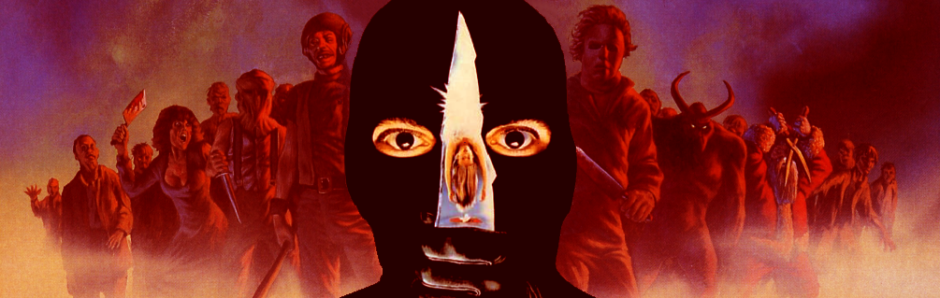

The movie was released in Italy on August 6 1983 and would become a modest success, despite its violence and its rejection by the television network causing minor controversy. For its American release, the film was renamed A Blade in the Dark, a title which Bava himself has admitted to preferring than its original counterpart, The House of the Dark Stairway. Lost among the countless slashers that were released in the early eighties, the film would soon slip into obscurity, despite being released on VHS. Bava would find greater acclaim with his splatter trilogy Demons, which would mark yet another collaboration with Argento, although A Blade in the Dark stands as his finest giallo film to date and one of the most underrated Italian thrillers of the era.

7 Responses to SPAGHETTI SLASHERS – A Blade in the Dark