This is a difficult one. Along with The Last House on the Left (1972), this is one of those unpleasant 70’s rape-revenge flicks that makes its audience feel dirty for watching a woman being brutalized, and then for cheering her (or her surrogates) on as she seeks revenge.

Camille Keaton (from What Have You Done to Solange? and Tragic Ceremony, and granddaughter of silent film comic Buster Keaton) is Jennifer, an author who rents a country cottage, planning to write and relax there. She’s harassed and raped by four men, one of them mentally challenged, and then (SPOILER ALERT) she tracks them down and kills them one by one. (END SPOILER ALERT) That, in a nutshell, is it.

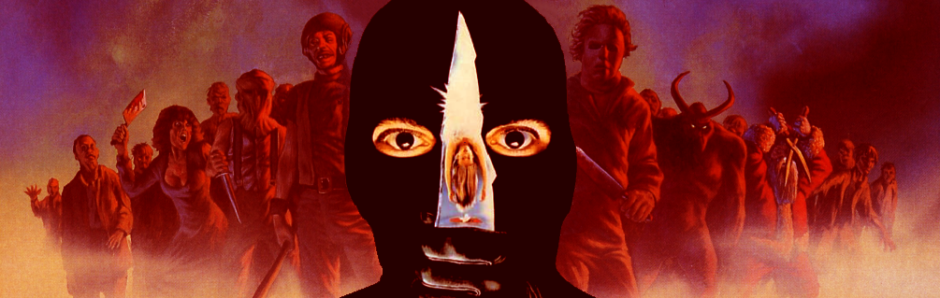

One of only two films directed by Meir Zarchi (the other being Don’t Mess With My Sister; 1985), I Spit on Your Grave is competently made, more so than The Last House on the Left. Its 2010 remake is even more polished, however, it’s neither as controversial nor quite as effective as the original, much like the 2009 remake of Last House.

So, what’s an appropriate reaction to the original I Spit on Your Grave? Disgust? Outrage? Dismissal? Enjoyment? What are we to take away from 100 minutes of rape and revenge? Is it the understanding that rape is bad? Hopefully that has always been obvious. Is it to learn that revenge is futile? The Last House on the Left at least makes it clear that it toys with this idea by adding a brief coda to emphasize this point, but I Spit on Your Grave doesn’t. Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971) clearly revels in its protagonist discovering his bloody “manhood” after his wife and home are attacked, adding a grey area to its resolution; I Spit on Your Grave is not so intentionally thought provoking. Bear with me. It’s through these comparisons to other thematically related films that we’ll discover a reading of I Spit on your Grave. By finding out what it’s not, it becomes easier to define what it is.

For example, Gaspar Noé’s Irreversible uses its rape scene to not just shock, but to also show how brutal and harrowing rape is. I Spit on Your Grave does that too, but in a much more questionable manner and for such a loooooong time. At least it’s not at all titillating, so thank God its intent doesn’t seem to be to sexually excite its audience. The prolonged rape scene isn’t even the single moment when ugly reality intrudes on an otherwise enjoyable exploitation flick like it is in, say, Savage Streets. There it shows us how vile the villains are and sets up the action that follows. Here too, it propels the film forward (eventually), but it also takes up almost a quarter of the film’s running time.

I Spit on Your Grave differs from even Deliverance, another 70’s rape-revenge film, because there is no sense of, well, deliverance. You sit there, wondering what kind of life Keaton’s character is going to return to? How is she going to explain all those bodies? What’s next? When I Spit on Your Grave is over, when it just ends like the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre, the viewer is left with only an emptiness. At least the ending of Chain Saw was somewhat cathartic as the audience felt like it had escaped from Hell along with Marilyn Burns, even if she would never quite be the same ever again. In Chain Saw, however, Burns didn’t become the monster; in Grave, Keaton does. Perhaps that’s the movie’s point – that the actions of the male characters have turned Keaton into a monster – but I don’t really think so.*

After all these comparisons to other rape-revenge films, what I’m left with are two reactions: 1) I Spit on Your Grave’s resonance and ability to disturb comes from it’s lack of point of view, it’s journalistic observation that sits back, shows what happens, and doesn’t comment on it. And 2) I Spit on Your Grave seems to exist purely as exploitation cinema. As true horror exploitation, its job is to take us somewhere dark, and that it does. And that makes I Spit on Your Grave impossible to dismiss.

*When discussing Keaton’s presence in I Spit on Your Grave, it’s important to note that the effectiveness of the film rests almost entirely upon her performance. If she appears a little lifeless at first (perhaps intentionally), as she endures what is infamously recognized as the longest rape scene in film history (approximately 25 minutes) and its resulting change in character, Keaton’s performance also changes into something much more vivid. And based on what Keaton is called upon to endure here as an actor, it’s almost impossible to separate the agony her character suffers from the agony Keaton must have actually encountered during shooting.

7 Responses to Review: I Spit on Your Grave (1978)