Long before he wowed fans with Freddy Krueger, thriller them with Scream and bored them senseless with Music of the Heart, filmmaker Wes Craven was producing low budget exploitation features in an attempt to shock and disgust audiences. Whilst the more successful of these was his second attempt, The Hills Have Eyes, perhaps his most notorious was The Last House on the Left, his directorial debut developed alongside fledging producer Sean S. Cunningham and loosely based on a Swedish Academy Award winner. Over the years, both Craven and Cunningham have attempted to justify its existence by stating that it was an allegory for all of the uncensored footage that had been broadcast by news networks during the Vietnam conflict, as well as a reaction against the bloodless violence of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and other sixties classics. But the truth was far less noble. The Last House on the Left was a cheap horror movie that would follow the typical rape/revenge formula whilst employing a documentary-style approach. In fact, the original draft of Craven’s script was a far cry from any kind of social commentary, featuring unnecessary elements of disembowelment and necrophilia. Plain and simple, The Last House on the Left was not art, it was trash.

Wesley Earl Craven was born on August 2 1939 in Cleveland, Ohio, to a strict working class Baptist family. After studying philosophy and literature at Wheaton College in Illinois, he earned a writing and philosophy Masters from John Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. He eventually became a lecturer in Humanities and English at Clarkson College in Potsdam, New York, where he would first develop an interest in cinema when, in 1968, he collaborated with a group of his students on a 6 millimetre short called The Searchers. As his passion for filmmaking grew, his desire to teach slowly diminished and by the end of the semester he decided to pursue his newfound ambition. After moving to New York City, Craven found that he was without work and trying to support a family and was forced to take a teaching job in a high school. But an old college student, Steve Chapin, had taken notice of his passion and suggested that he meet his brother, Harry. The following summer he took him up on his offer and went out to meet Harry Chapin, who at the time was making industrial films for the likes of BMI. During this period, Craven was taught the basics of filmmaking from an editorial point-of-view, where he would learn the importance of post-production, whilst also working part-time as a taxi driver. Harry Chapin would later become a successful singer-songwriter, penning such classics as Cat’s in the Cradle, before dying tragically in an automobile accident on July 16 1981. Craven’s odd-job lifestyle would eventually cost him his marriage, leaving him broke and alone. It was whilst struggling on occasional work synching up dialies that he would make the acquaintance of another wannabe filmmaker.

Sean Sexton Cunningham was a native of New York, having been born there on December 31 1941. After attending Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, he began to entertain a career as a doctor, but soon discovered that he was taking more pleasure from his part-time theatre work and so studied film and drama at Stanford University. A friend from the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts offered him work as a dresser but soon began to take notes from the stage manager, eventually taking the role himself with The Merry Widow at the Mineola Playhouse on Long Island. His two successful productions, The Front Page and Our Town, had earned him a modest amount of money and so he decided that his next step should be into the film industry. Knowing nothing about the process of making movies, he decided that he would learn as he went along and so raised $3,500 to produce a sex-education feature, The Art of Marriage, for which he would credit himself as the Nevada Institute for Family Studies. With his profits, he rented out office space in Manhattan where the city’s independent film scene was thriving. Creating the label Sean S. Cunningham Films/Lobster Enterprises, he and a few friends would create a series of commercials in an effort to develop their own filmmaking style. With a further $50,000 raised from friends and family, Cunningham’s next project was a pseudo-documentary that was once again marketed as adult education.

Karma Sutra, which would mark the first appearance of soon-to-be porn star Marilyn Chambers (who sadly passed away on April 12, ten days shy of her fifty-seventh birthday), began shooting in May 1970, although a a four month hiatus would push the wrapping of the production back until the end of the year. Filmed in Cunningham’s home town of Westport, Connecticut, Cunningham found that constant creative differences with his business partner, Roger Murphy (who had previously worked as a cinematographer on Monterey Pop, a 1968 film that covered the Monterey International Pop Festival in California), were becoming an issue, particularly during post-production and soon he was forced to find additional help during the editing process, finally settling on Craven. With Murphy constantly walking from the project, Cunningham found he had to rely more and more on his new assistant, which would result in a close friendship and a re-shoot in Puerto Rico during the winter would mark Craven’s official debut as a director, albeit uncredited. Once completed, Cunningham began to shop his new project, now retitled Together, around potential distributors, eventually travelling to Boston to meet the owners of a company called Esquire Theaters of America, who had recently made the decision to branch out into film development and distribution under the banner Hallmark Releasing Corporation. The businessmen, Philip Scuderi, Steve Minasian and Robert Barsamian (along with assistance from their theatre booker, George Mansour) negotiated a deal and paid the producer $10,000.

The early seventies saw a rise in erotic cinema, with the likes of Deep Throat and Emmanuelle scoring big at the box office. Between Hallmark and AIP, who would distribute the film nationally, both companies would earn millions in profit from the film and soon the owners approached Cunningham about developing a low budget horror film, as they seemed a quick and easy way to make money, offering him $50,000. Sensing the enthusiasm and obvious talent in his protégé, he offered Craven the chance to write and direct, with Cunningham’s office having the necessary equipment to shoot it cheaply. Having recently seen Jungfrukällan (The Virgin Spring), a Swedish drama from acclaimed auteur Ingmar Berman that told of a group of goat-herds rape and murder the daughter of a farmer, only to later take shelter in the family home where they are discovered and revenge is brutally served, Craven took the basic outline and brought it into modern times, where two hippie girls on their way to a rock concert and kidnapped, tortured, humiliated and murdered by a gang of escaped criminals. His script, initially titled Night of Vengeance, featured an onslaught of tasteless set pieces in which the girls are abused in every possible way, due to Cunningham’s insistence that Craven pull out all the skeletons from his closet. One scene featured two of the convicts performing necrophilia on one of the girls, whilst the female of the gang removed the other girl’s eyeballs and crushed them underfoot, before slicing off her nipples and cutting her stomach open, dragging out her intestines and then watching as her friend sodomises the corpse. Any kind of social commentary that Craven had intended was lost amongst the pure exploitation.

With the first draft completed in just two weeks, Cunningham would assist in the rewrites, removing much of the extreme gore and improving the dialogue. Another aspect of the script changed during this process was the finale. Originally, the father (who was a doctor) was to have a scalpel fight with the lead convict, but after Cunningham noticed a poster in Times Square of two men battling with chainsaws he decided to incorporate that into their story. Having hardly made any money from Together, Cunningham was determined to make a profit with their feature film. When the two submitted the script to Hallmark, the investors were so enthusiastic at its potential they offered a further $40,000. Pre-production on what had become Sex Crime of the Century (although throughout the shoot the name would constantly revert back to its original name) began in August 1971. As the feature was a non-union film, the producers were forced to publicise their casting call in any way possible, usually through word of mouth. The most experienced of the cast was Fred Lincoln, born Fred Perna in Manhattan, later growing up in the Hell’s Kitchen neighbourhood of New York. Lincoln was a veteran of countless X-rated movies (such as The Altar of Lust, Millie’s Homecoming and Pay the Baby Sitter), as well as a stunt gig on The French Connection. For his callback, he was accompanied by a young friend, twenty-three year old Jeramie Rain, who read for the role of Sadie, one of the sadistic criminals. Despite the filmmakers originally writing the character as a forty year old, Cunningham was finally convinced and offered her the role. Incidentally, Rain would marry fellow actor Richard Dreyfuss in 1983, eventually divorcing in 1995.

For the role of Krug, the lead villain, a quiet and polite man by the name of Martin Kove arrived at the auditions, before stating that he was not right for the part and requested for the comic relief role of the deputy. Instead, he suggested his girlfriend’s brother, a musician and occasional actor called David Hess, who arrived for his audition unprepared and in an aggressive mood. Suitably impressed, Craven and Cunningham hired him on the spot. The other main roles went to an assortment of newcomers, including Lucy Grantham, Eleanor Shaw (who was credited as Cynthia Carr), Marc Sheffler and Sandra Cassel. Principal photography commenced on October 2 1971, once again in Westport, with Cunningham using his house and surrounding area as the various locations. The days were long and unpleasant, particularly for Cassel who seemed disgusted by the experience. Due to the lack of funds, the movie was shot without permits, with the crew filming a scene and then quickly moving onto the next set-up before police could be alerted. Among the many local youths who had been drafted in to help out with the production was twenty year old Stephen Miner, who would later launch his own career directing the likes of Friday the 13th Part 2, Halloween H20 and the recent Day of the Dead remake.

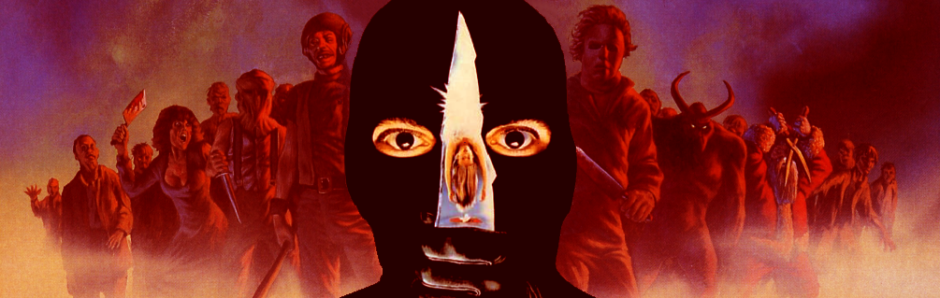

The shoot eventually wrapped on November 6, with Craven and Cunningham rushing straight into post-production, with the editing process taking approximately six months to complete. Many scenes were cut in different ways, resulting in the long lost edit that became known as Krug and Company (which was finally released by Anchor Bay in 2003), whilst the theatrical cut was released on August 30 1972 under the alternative title The Last House on the Left, at the suggestion of Hallmark. Their ingenious marketing campaign played a large part in the film’s success, with its infamous slogan, ‘To avoid fainting keep repeating, it’s only a movie,’ gracing the movie poster. Hallmark were hitting their stride by 1972, also releasing the likes of Mario Bava’s bloody thriller Reazione a catena, which they retitled Twitch of the Death Nerve for its US release. The Last House on the Left would make around $3m in the United States, before earning an impressive $10m worldwide. But, despite the attention the film received, those involved were quick to distance themselves from such smut. Cunningham attempted several family movies before returning to the genre with Friday the 13th in 1980, Craven constantly tried to escape the horror typecast that his early work had placed upon him, whilst most of the cast would retire from the industry soon afterwards. Almost forty years later, The Last House on the Left is still one of the most controversial and deeply unpleasant movies ever directed by a mainstream filmmaker.

3 Responses to It’s Only a Movie: The Last House on the Left (1972)