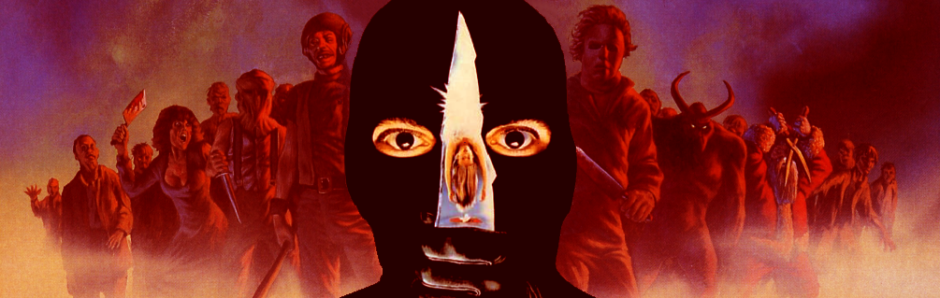

Michael Myers had an axe, Leatherface had a chainsaw and Jason Voorhees had whatever was lying around – yet one of the most grizzly murder weapons used in the vintage days of exploitation was the flamethrower, the weapon of choice for Donny Kohler, the disturbed antagonist from Don’t Go in the House. Released amid the onslaught of low budget slashers that populated the drive-ins during the early 1980s, Joseph Ellison’s feature debut was a grim and unpleasant Oedipal thriller that depicted a young man whose abusive mother suddenly passes away, leaving him unable to deal with the grief and so he begins to take his frustration out on a succession of unsuspecting women. Don’t Go in the House became infamous in the United Kingdom during the mid-’80s when it was labelled as a ‘video nasty’ and faced prosecution, only further fuelling its reputation and arousing the interest of young bloodthirsty audiences.

Following his studied at New York University, New York-born Joseph Ellison worked as a post-production assistant whilst developing his own 8mm short films. Whilst location scouting in New York for a flick called Pelvis, Ellison met his wife-to-be, Ellen Hammill, who would become a major driving force in his subsequent filmmaking career. In the fall of 1978, a low budget flick called Halloween would take the country by storm, convincing every wannabe director to grab a camera and shoot their own movie. Thus, Ellison decided to make a horror, something that could be produced relatively cheaply and sold at drive-ins. He began searching for a concept that would be idea for a first-time feature and eventually met Joe Masefield, who had cut his teeth as a production manager on such ’60s trash as Lash of Lust and Sin, You Sinners, before working as a sound editor on Naked Came the Stranger and, much later, The Evil Dead.

Masefield had no prior experience as a writer but he had a treatment, The Burning Man, about a man who had been abused by his mother and punished by being burnt, only to grow up and punish other women by burning them alive with a flamethrower. Whilst Ellison found Masefield’s style a little pedestrian, he knew that the concept would make an effective horror and began reworking it with the help of Hammill. They began researching child abuse in an effort to make their principal character more believable and began location scouting whilst writing the script, often developing scenes with specific rooms in mind. They eventually found the ideal house whilst searching through Atlantic Highlands in New Jersey and decided immediately that this would be the setting for their film. Soon the script was completed and Masefield, along with Dennis Stephenson and Matthew Mallinson (who had been working as Hammill’s assistant), began to raise the necessary budget whilst Ellison focused on pre-production.

Although he had made use out of a 16mm Arriflex camera he had borrowed from a production company for his earlier shorts, Ellison knew that for a feature he would need to shoot on 35mm. With the help of a producer, Dick DiBona, who had assisted many young filmmakers along their way, Hammill had succeeded in acquiring a camera. Unfortunately, the company did not approve of Ellison working out of their studio and so he was forced to resign from his job. Further troubles came when Masefield decided to back out of the project, forcing Hammill to take a more hands-on approach as producer. The production was further hampered by the Screen Actors Guild strike that began in December 1978, just as the movie was to enter production, causing the industry to almost grind to a halt. The dispute had been caused by objections over television commercials and, whilst their feature was not strictly a union project, the effects would cause a ripple throughout the entertainment business.

For the lead role of Donny, Ellison cast Dan Grimaldi, whom he had met whilst at NYU and had become close friends. Grimaldi had also provided voice work for Ellison’s various dubbing assignments and, although the character was not written with someone like Grimaldi in mind, Ellison knew that he could make the part his own. Grimaldi would later enjoy acclaim for his recurring duo roles as Philly and Patsy Parisi on the hit show The Sopranos. Perhaps the most unpleasant part in the movie was that of Kathy Jordan, Donny’s first victim who is strung up naked and burnt to death with a flamethrower. Hammill had met a young model at Hunter College called Debra Richmond, who worked as a Playboy Bunny and had appeared nude for various photo shoots. More than happy to strip for the camera, Ellison was impressed by Richmond’s courage, who would be listed on the credits as Johanna Brushay.

Whilst co-star Charles Bonet had previously appeared in Bruce Lee: The True Story, most of the remaining cast would make their screen debut with Don’t Go in the House. Behind the camera, the cinematography was handled by Oliver Wood, whose work for the BBC was followed by a relocation to the United States, where he would lens such schlock as The Honeymoon Killers. His subsequent career would include a string of blockbusters: Face/Off, The Bourne Identity and Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby. The special effects were designed by Tom Brumberger (who passed away in 2006), who suggested to Ellison that he hire models or dancers as the victims as they would be skinny enough to apply make-up onto in order to the resemble charred corpses. His assistant on the special effects was Matt Vogel, who would later work on such cult flicks as Alone in the Dark, C.H.U.D. and Street Trash.

Filming concluded in February 1979 and Ellison began cutting the movie in his home. After a disappointing screening for Terry Levene of Aquarius Releasing, the film was cut by approximately twenty minutes, taking the running time down to just over eighty minutes. Don’t Go in the House was released theatrically by Film Ventures International in 1980, at the height of the slasher boom and the moral backlash against misogynistic horror films. In the UK, the film received further cuts on November 13 1980 to gain an X-rating. Its distributor, Arcade, then released the uncut version on home video, which resulted in the movie falling foul of the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) and the BBFC. The movie was finally re-released on March 30 1987 with a running time of just short of seventy-six minutes (resulting in a further three minutes and seven seconds worth of cuts) and was granted an 18 certificate.

7 Responses to The Burning Man: The Making of Don’t Go in the House