The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 had proven to be the third financial failure in a row for both director Tobe Hooper and Cannon Films, who had entered into a rather dubious three-picture deal following his exit from The Return of the Living Dead. With the rights available once again, New Line Cinema optioned to produce the second sequel to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and met with Hooper to discuss story ideas, although his commitment to another project, Spontaneous Combustion, would eventually force him to step down. Kim Henkel, Hooper’s co-writer on the original movie, would also attend a production meeting but soon realised that executives at the studio had little interest in what he had to offer. New Line’s Michael De Luca, an avid reader, had already become seduced by the writings of a young author called David J. Schow and, after his brief involvement with A Nightmare on Elm Street 5 (which he had dubbed Freddy Rocks) resulting in him being replaced by more experienced screenwriters, Schow completed work on an episode of the small screen spinoff, Freddy’s Nightmares.

This would convince both De Luca and producer Kevin Moreton to offer Schow the task of developing The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III. In an ironic twist of fate, Schow signed a deal with New Line to write the script on Friday the 13th, in January 1989. For the next two weeks, ideas were passed back and forth with executives, with Schow suggesting that the character of Leatherface have the mentality of a teenager; rebellious, moody and unpredictable. The first draft was submitted two months later, with Schow inserting several scenes of extreme violence that he intended on toning down during the subsequent rewrites. But no sooner had he completed one draft, producers at New Line began sending notes through which instructed him that certain aspects of his script could be considered offensive, whilst they also expressed concern over Schow’s decision to add a sympathetic side to Leatherface, instead of merely being a generic slasher villain.

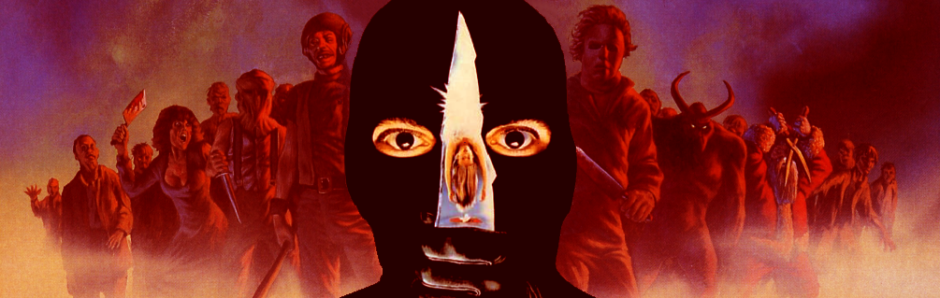

Despite outside interference, Schow’s enthusiasm for the project had resulted in him drawing sketches of how Leatherface resembled in his script, even showing special effects artist Greg Nicotero during a visit to Fangoria’s Weekend of Horrors. Nicotero and his newly formed company KNB EFX had managed to secure work on the production, as well as A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child, which had laid the foundation for a long and lucrative collaboration with New Line. Even as Schow neared the end of his rewrites, a director had still not been hired for the shoot, although he had suggested FX artists Tom Savini and Rob Bottin as potential candidates. With the production date being pushed back a month from June, producer Jeff Schechtman was fired and replaced by Robert Engelman, whose prior credits had included The Serpent and the Rainbow and Shocker for Wes Craven. This shift in producers would become an issue throughout the production, with a new set of ideals and opinions clashing with those already established.

Even as principal photography drew closer, New Line had been unable to commit to a director, although countless names were passed around as possibilities. Amongst the shortlist were Peter Jackson, whose work on the low budget Kiwi cult splatter Bad Taste had prompted the studio to offer him their fifth A Nightmare on Elm Street movie, although he would eventually pass on both projects. Other potential candidates included John McNaughton, whose thriller Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer had fallen foul of the censors a few years earlier, David Blyth (recently fired from The Horror Show, later released as part of the House series) and Jonathan Betuel, although the latter would be forced to remove himself from negotiations after only three days due to commitments to the popular television show Alien Nation. Eventually, after a screening of Stepfather II, De Luca finally settled on its director, Jeff Burr.

Due to no director being attached for the majority of pre-production, Schow had not received any feedback from anyone involved with the actual filming of the movie, although his creative freedom was about to come to an end. Both Engelman and Burr took it upon themselves to rewrite the script prior to shooting, with Engelman toning down most of the violence, whilst both reworked much of the dialogue. With the material being passed back and forth between producers and Burr, continuity and character began to suffer, with Schow growing increasingly frustrated with being pushed out of the loop. Disappointed with their own efforts, they began reinserting Schow’s dialogue back into the script, causing further issues with the structure and tone, constantly shifting between dark and comedic. By the time that Schow received a copy of the final draft, his original concept had become watered down and more suited to New Line’s particular brand of horror, which would contrast against his own more brutal style of work.

Unlike many writers, Schow was present on set for the majority of the shoot and, despite feeling disappointed with the script, was impressed with the quality of acting that was on display, particularly from heroine Kate Hodge and lead antagonist Viggo Mortensen. Even as the cameras were rolling, producers constantly changed plot points, forcing Burr to rewrite or even reshoot sequences. Amongst some of the more drastic changes was the fate of Benny, portrayed by Dawn of the Dead‘s Ken Foree. Although he was originally to have perished, New Line’s president, Robert Shaye, had decided that he should survive and insisted on his character coming back at the end of the story. The tampering would show in both box office figures and reviews, with the Washington Post stating, “All too much of III is rehashed horror. The first installment was genuinely shocking, unrelenting, visceral terror… Sure, there are more bare bones cluttering the secluded family dwelling than there are at the Museum of Natural History, but that’s a plot problem as well.”

5 Responses to David Schow’s Leatherface