With Halloween 2 set for release later this year, Retro Slashers looks back on the life and career of the man responsible for the original classic,

JOHN CARPENTER.

There are very few filmmakers who so spectacularly fell from grace like one-time master of suspense John Carpenter. For ten brief years, Carpenter enjoyed a successful run of science fiction and horror classics including Assault on Precinct 13, Halloween, The Fog, Escape from New York and The Thing, before his train came to a grinding halt in the early ’90’s with such missteps as Memoirs of an Invisible Man and Escape from LA. Since then, he has kept a low profile with a string of independent flops that only serve to reinforce how inferior his later input really was. Regardless, his loyal fanbase have helped keep his name alive with various websites, forums and other such tributes, helping to remind audiences just how great a John Carpenter movie can be. It is frustrating to think that the man responsible for the creation of such a horror icon as Michael Myers could also produce soulless B-movies like Vampires and Ghosts of Mars, but when all the ingredients come together the end result can be nothing short of perfection. And with several promising projects currently in development, and a career that spans almost four decades, Carpenter is one of the most important names in horror cinema.

John Howard Carpenter was born in Carthage, New York, on January 16 1948 to Howard, a music lecturer and session musician, performing alongside such greats as Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley. In 1953, the Carpenters would relocated from New York to Bowling Green, the fourth largest city in the state of Kentucky. John would develop two major interests as a child, one would be to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a musician while the other was an increasing obsession in cinema. Inspired by such greats as Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock, Carpenter started to make 8mm shorts while still at school, experimenting with such genres as horror and science fiction, which had come into its own in the 1950’s with such seminal classics as The Day the Earth Stood Still and Forbidden Planet. Having also developed a taste for special effects like stop motion, his early efforts included such titles as Revenge of the Colossal Beasts, Sorcerer from Outer Space and Gorgon the Space Monster which, while being poorly made and lacking the genre-bending style that he would employ in his later work, still featured certain themes and elements that would become a staple of a Carpenter picture. Sadly, he has stated that these shorts will never been shown in public or released commercially.

After graduating from high school, Carpenter briefly attended Western Kentucky University, before transferring to the prestigious University of Southern California (USC), where he would further develop his talents. The USC played host to such industry guests as Hitchcock, Hawks and even Orson Welles and was the perfect environment for a wannabe filmmaker. It was here that Carpenter would make his first creative steps, collaborating with classmates James Rokos and John Longenecker on a 16mm short entitled The Resurrection of Broncho Billy, which told of a modern day cowboy (Johnny Crawford) who dreams of living in the Wild West. Carpenter would work as a co-writer, editor and composer, as well as supporting Rokos with directing, teaching him early on the importance of multitasking. Once completed and showcased, the print was blown-up to 35mm and briefly distributed theatrically by Universal Studios, eventually winning an Academy Award for Best Short in 1970, a major achievement for a student film.

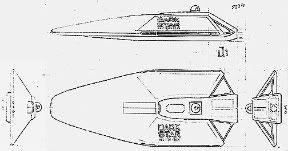

For his master’s thesis, Carpenter would develop a spoof of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, a recent blockbuster and major milestone in science fiction cinema, with fellow student Daniel O’Bannon. Pitched by Carpenter as ‘Waiting for Godot in Space,’ the concept for their fifty minute film would see a group of bored astronauts wandering the galaxy aimlessly on a mission to destroy unstable planets to make space for future colonisation. Their project, Dark Star, would become a labour of love, with both Carpenter and O’Bannon taking on various duties in order to keep the film afloat. Drafting in The Resurrection of Broncho Billy co-writer Nick Castle (who would later play an important role in several of Carpenter’s most successful movies) as assistant cameraman, Dark Star would also mark the first appearance of another Carpenter regular, art director Tommy Lee Wallace. O’Bannon would not only help Carpenter (who would make his directorial debut here) write the screenplay, but also worked on special effects, editing and set designing, as well as taking one of the principal roles. Carpenter, meanwhile, would produce and compose the score.

To help with their minuscule budget, the filmmakers would raid the trash of their family and friends to scavenge props for the sets. For the alien which the crew have been keeping as a pet, a beach ball was used, with hands glued to the sides. This basic approach to the FX helped give Dark Star a certain charm and despite its simplicity, the alien still somehow manages to have character. The special effects were created by O’Bannon and Ron Cobb, both of whom would later collaborate on the sci-fi blockbuster Alien in 1979. The models were constructed by Gregory Jein who would later provide a similar duty on the hit TV show Star Trek: The Next Generation, while the matte paintings were provided by Jim Danforth of When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth fame. O’Bannon’s co-stars were made up of other first timers, with Brian Narelle, Dre Pahich and the late Cal Kuniholm portraying Doolittle, Talby and Boiler, respectively, while O’Bannon would take on the most comical role as Pinback, who would be charged with babysitting the alien.

By the time Carpenter and O’Bannon had graduated in 1971 they had decided that they would expand their fifty minute film into a feature length movie. USC classmate Jonathan Kaplan donated $10,000 to help keep Dark Star in production, though this contribution was blown on one sequence, where Pinback was terrorised by the alien while hanging on for his life in the elevator shaft. This effect was achieved by O’Bannon lying on his stomach and moving his legs as if he is suspended above the shaft while crew members pushed an elevator across the floor towards him. Kaplan would receive an ‘associate producer’ credit for his gesture. After almost two years of struggling to complete the picture, the filmmakers managed to arouse the interest of Jack H. Harris, a former publicist and distributor who had moved into production with Steve McQueen’s 1958 sci-fi The Blob. Carpenter was determined to not only expand his film but also transfer the print from 16mm to 35mm for theatrical release, and so forfeited ownership of the movie in exchange for funding, with the budget eventually reaching $60,000. By the time the filming was complete, the cast were forced to wear wigs as their hairstyles had changed so much over the four years since production began, and most of those involved were no longer on speaking terms. To make matters worse, there was some bad blood between Carpenter and O’Bannon after the latter felt that he had not received the recognition he deserved in the credits.

Once the editing was complete, Harris attempted to release the movie himself before eventually selling the rights onto Bryanston Distribution, who had recently given Andy Warhol’s Flesh for Frankenstein a theatrical run. With no publicity or recognisable names attached, Dark Star quickly sank without a trace. O’Bannon would later work as a computer animator on Star Wars before co-writing Ridley Scott’s breakthrough movie Alien, which would borrow heavily from his first feature. Carpenter, meanwhile, attempted to make his way into the industry as a writer, developing screenplays that would later be adapted by other filmmakers, with the first sold being Bad Moon Rising, which would be produced a decade later. One of these scripts, Siege, would be optioned with Carpenter attached as director. This would mark his commercial debut and would see him collaborate with several actors who would later reappear in much of his work, including Charles Cyphers and Nancy Keys, who would be credited as Loomis. This would also see Carpenter and producer Debra Hill start what would become a very successful relationship, both professional and, to a lesser extent, personal.

One of Carpenter’s all-time favourite movies was Howard Hawks’ 1959 Western Rio Bravo, starring screen legend John Wayne as the sheriff of a small town who must fight alongside his drunken deputy and a cripple in order to stop a prisoner being sprung by his outlaw brother. Keeping the basic formula but updating it to modern-day Los Angeles, Carpenter’s script saw Lieutenant Ethan Bishop (played by Austin Stoker) under attack on his first night at a closing precinct by a deadly gang known as Street Thunder who seek vengeance against one of the men in the station who was responsible for the death of one of their numbers. Siege would have several aspects to its story which would make it stand out over its contemporaries. First of all, the character of Bishop is a black man, someone who would normally be reduced to a sidekick stereotype, but thanks to George A. Romero’s 1968 zombie classic Night of the Living Dead a black lead was now acceptable. Surprisingly, Bishop’s greatest ally during the crisis is the notorious criminal ‘Napoleon’ Wilson (the late Darwin Joston, who at the time was Carpenter’s neighbour), who is locked in a jail cell when the gang first attack. It is this odd couple pairing that lies at the heart of not only this script but much of Carpenter’s work.

When Siege was submitted to the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America), the censors took exception to a scene where a young girl is senselessly murdered by a gang member when she unwittingly witnesses an execution. Despite not being particularly graphic, the sequence was trimmed in order to avoid the dreaded X-rating. After attending a screening at the Milan Film Festival, independent producer Irwin Yablans approached Carpenter with an offer of distributing the film through his company, Compass International. His only insistence, though, was that the name of the film be change, and eventually he suggested Assault on Precinct 13. Its brief run in America did little to attract attention but once it was screened at the 21st London Film Festival in 1977 it received critical praise, with further showings around Europe helping to raise its profile. Assault on Precinct 13 would become Carpenter’s calling card and bring him to the attention of various Hollywood studios and producers.

For his next project, Carpenter would take his first step towards the horror genre, with the TV movie Someone’s Watching Me. A suspenseful thriller in the style of Hitchcock, Carpenter once again wrote and directed the piece, though this time he would be replaced by a different composer. The story centred on a prowler that watches the apartment block across from his window and eventually sets his sights on a new tenant after his last obsession committed suicide. From the film’s opening credits to its dry humour and claustrophobic cinematography, Someone’s Watching Me immediately recalls such Hitchcock classics as Rear Window and Vertigo. Despite the screenplay initially being written as a feature film, Warner Bros. offered Carpenter the chance to develop it for television instead. Unlike most of his projects, Carpenter was unable to hire his regular cast and crew, though Assault on Precinct 13’s Charles Cyphers would appear in a small role.

The basic premise of Someone’s Watching Me centres on TV director Leigh Michaels (Lauren Hutton), who has moved into Arkham Towers, a luxurious Los Angeles apartment block. But a stalker is watching her through his telescope and has started following her everywhere she goes, but the more she tries to evade him the closer she comes to fall into his trap. Shot under the alternative title High Rise, Carpenter shot Someone’s Watching Me for Warner Bros. Television and would be the first time that he would have to work under strict guidelines, though he was still allowed a certain amount of artistic freedom. During the shoot, Carpenter would strike up a relationship with one of his leading ladies, Adrienne Barbeau, who portrayed Leigh’s studio assistant Sophie. The two would marry the following year. The film was first screened on NBC on November 29, 1978 and would receive positive reviews, marking another victory for the director.

Despite Someone’s Watching Me’s minor critical success, Carpenter seemed unable to find a suitable feature film that he could direct himself, so when Dark Star producer Jack Harris offered to help sell his spec script Eyes he reluctantly agreed. Harris took the story to Jon Peters, who was the head of Columbia Pictures and manager of actress and singer Barbra Streisand. Peters agreed to purchase the script as a vehicle for his client, requesting that Carpenter change certain aspects of the protagonist so it would suit her personality. Carpenter obliged, though he found the experience frustrating, eventually being replaced by David Zelag Goodman. The final result would bear little resemblance to Carpenter’s original vision, though Streisand would back out of the project due to the risqué nature of the story and was replaced by Chinatown’s Faye Dunaway. Despite mixed reactions from the press, the film would make around $20m, though it would do little for the careers of anyone involved.

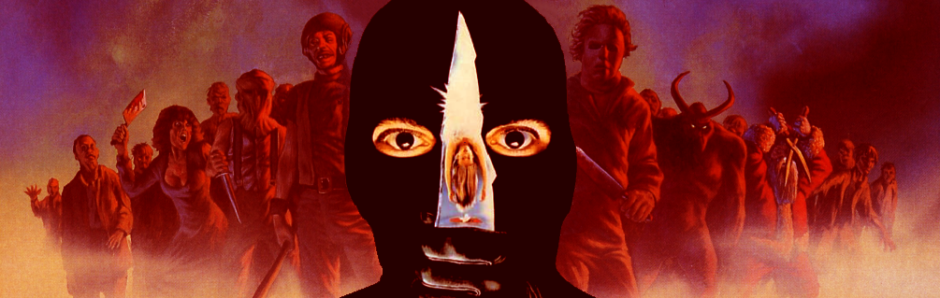

After the negative experience of The Eyes of Laura Mars, Carpenter was desperate to once again direct a feature film. Yablans had been impressed enough by Assault on Precinct 13 to consider the young filmmaker for his next project, a low budget horror movie about a babysitter stalked by the boogeyman. Carpenter saw potential in the premise and agreed to the offer as long as he could have full control. Reuniting with producer Hill, the two began to develop a script which, at Yablans’ suggestion, would be set on one night to help keep costs down. Initially titled The Babysitter Murders, Yablans eventually decided that the setting, and thus the title, would be Halloween. To help with finance, he approached Syrian producer Moustapha Akkad, fresh from the controversial Mohammad, Messenger of God. Carpenter had agreed to bring the movie in at less than $300,000 but Akkad was unconvinced that the relatively inexperienced director would be able to fulfil his claims, but after meeting the young filmmaker to discuss the project he agreed.

During the writing of the script, Hill mainly focused on the teenage characters that would be the victims of the masked maniac while Carpenter concentrated on the evil aspects of the story. Yablans’ only instructions during the writing process was that he wanted the script to work like a radio show, with ‘boos’ every ten minutes. The antagonist, Michael Myers, was named after the head of Miracle Films, a company which had helped in the distribution of Assault on Precinct 13, while his adversary, Dr. Sam Loomis, took his moniker from a character from Hitchcock’s classic Psycho, a major influence on the movie. The heroine, Laurie Strode, was a tribute to one of Carpenter’s ex girlfriends and the town in which it is set, Haddonfield, was also the name of a place in New Jersey where Hill grew up. For the role of Loomis, Carpenter initially approached Hammer stars Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, who both declined (though Lee would later state that it was the worst mistake of his career). A copy of the script was eventually sent to British actor Donald Pleasence, who the director was also a fan of. To his surprise, he accepted. The part of Laurie was originally offered to Battlestar Galatica’s Anne Lockhart, though when negotiations fell through the role was instead filled by TV actress Jamie Lee Curtis who, coincidentally, was the daughter of Psycho star Janet Leigh. The part of Myers would go to Dark Star collaborator Castle, who reportedly received a mere $25 a day for his work.

For directing, writing and composing the score, Carpenter’s fee was $10,000, though he would also receive a share of the profits if the film was a success. For Myers’ visage, the director wanted his villain to have a plain-yet-creepy presence, and sent his art director Wallace out scouting for masks. When he returned he showed off two to the crew – one was a clown’s face, and the other was a $1.98 Captain Kirk mask which Wallace had spray painted white and cut bigger eye holes into. The image unnerved all present and Carpenter knew that he had what he needed. Principal photography commenced in the spring of 1978, despite the story being set in October (forcing the crew to have to improvise with the autumn look), and lasted twenty-one days, with Pleasence only being on set for five. Halloween premièred a few months later in Kansas City on October 25 and, due to Yablans being unable to afford a nationwide simultaneous release, would go from town to town to show the movie. By the end of its long run it had made an astonishing $47 in the States alone, making it one of the most successful independent movies of all time.

Carpenter’s next project would seem like a bizarre choice, though from a critical standpoint a wise one. Returning back to TV movie territory after Someone’s Watching Me, his 150 minute biography Elvis would chart the Vegas comeback tour of The King, originally broadcast a mere two years after his death. Elvis would mark Carpenter’s first collaboration with actor Kurt Russell who, back in 1979, was desperate to shake off his lightweight Disney image. Having made his feature debut alongside Elvis Presley in It Happened at the World’s Fair, it would seem somewhat ironic that sixteen years later he would come to portray him. Another bizarre coincidence was that in his last movie Change of Habit, Presley played a character by the name of Dr. John Carpenter. Russell had spent the 1970’s playing minor league baseball whilst struggling as an actor before he came to Carpenter’s attention.

Elvis wisely avoids the later years of the singer’s life and instead focuses on his early career and later comeback, with Russell managing to give a sincere and convincing portrayal without resorting to parody. The movie was produced by ABC as a mini series (clocking in at around two and a half hours) and would make its debut on 11 February 1979. While it was a given that the film would attract some attention, it became a surprise success and would become the highest rated TV movie up until that point. Told predominately in flashbacks, the formula that Carpenter employed would be used in later biographies such as the Johnny Cash story Ring of Fire. Elvis was a satisfying experience for both Carpenter and Russell and the two would work together again on a further four films. After Elvis, Carpenter would once again return to the horror genre after signing a two-picture deal with AVCO-Embassy.

Whereas Halloween had been a straight slasher, Carpenter’s next film would combine that style with an old fashioned ghost story to create a slow burning yet atmospheric tale of supernatural revenge. Inspired by a visit that Carpenter and Hill had made to Stonehenge during their visit to England while promoting Assault on Precinct 13, where they saw an eerie fog in the distance. Another influence was The Trollenberg Terror, a 1958 British science fiction movie which saw strange creatures materialising in a radioactive cloud. The pair started work on a story that would see the quiet coastal town of Antonio Bay fall under siege on the centennial anniversary of a mysterious disaster. As a strange fog engulfs the land, figures appear and hack away at the locals with their fishing hooks. It is later revealed that these are the haunted spirits of men who were murdered by the founders of the town and now their descendants are paying for their crimes.

The screenplay took a little over a month and was completed in March 1979. The cast was once again made up of Carpenter regulars – Jamie Lee Curtis, Adrienne Barbeau, Charles Cyphers, Nancy Loomis – and many characters were named after cast and crew that he had previously worked with – Nick Castle, Dan O’Bannon, Tommy Wallace. In the role of the central antagonist, Blake, was special effects artist Rob Bottin. The Fog was shot on a budget of approximately $1m between April and May 1979 at Raleigh Studios and Point Reyes, California. Upon viewing the final cut, Carpenter was less than impressed with the movie and decided to reshoot and add new scenes, resulting in a third of the theatrical cut consisting of new footage. When the film was released it would become another hit for the director, making around $21m on a $1m budget. With AVCO-Embassy having signed Carpenter on for another project, he began to work on an idea called The Philadelphia Experiment but when the script fell apart he optioned another story instead.

Back in the mid-1970’s, when Carpenter was frantically trying to sell his screenplays, he conceived a story about an outlaw named Snake Plissken who is sent into the ruins of New York City in order to rescue the president. Having been blackmailed by the officials, Snake is forced to carry out their mission, despite having nothing but distaste for the government. Carpenter wrote the script in the wake of the Watergate scandal, where it was revealed that various criminal activities had been carried out by order of President Nixon, which resulted in his resignation in 1974. Unfortunately, though, he was unable to gain studio interest and instead opted to make Assault on Precinct 13. By 1980, the success of Halloween had given the thirty-two year old filmmaker a little more credibility and finally he was able to realise his vision. He brought in old friend Nick Castle to help rewrite the script. Despite Avco-Embassy insisting on Charles Bronson or Tommy Lee Jones (who had starred in The Eyes of Laura Mars) for the role of Snake, Carpenter was concerned that hiring Bronson would cause too many issues with the experienced actor taking orders from a nobody and instead chose to go with Elvis star Russell.

Russell’s performance as Snake conjures up several classic actors, most notably John Wayne and Clint Eastwood. Perhaps as an in-joke, Carpenter hired Lee Van Cleef (who had co-starred with Eastwood in For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly in the 1960’s) in a small but pivotal role. Escape from New York was budged at $7m and would boast possibly Carpenter’s most impressive cast to date. Aside from the return of Pleasence after their collaboration on Halloween, the movie also saw appearances from Ernest Borgnine, Isaac Hayes and Harry Dean Stanton. Due to complications – both financial and political – filming in New York was near impossible for the entire shoot, and after various attempts from production designed Joe Alves to find a suitable location it was suggested by producer Barry Bernardi that they film in St. Louis, Missouri. A fire in 1977 had resulted in several blocks in the downtown area being near destroyed, proving an ideal place to shoot the ruined city. It is worth noting that the scene where a helicopter flies over Central Park features a matte painting in the background designed by New Work Pictures effects artist James Cameron, who would later become a successful director with The Terminator and Titanic. When Escape from New York was released in the summer of 1981 it made an impressive $25.2.

With Halloween playing a large part in the slasher boom of the early 1980’s, it was perhaps inevitable that a sequel would eventually follow. Carpenter was asked if he would return as director but declined, stating that he had no desire to remake the same movie again. Instead, he would once again co-write the screenplay with Hill, though the revelation of Laurie being Michael’s sister came from a self-confessed episode of writer’s block. Carpenter initially offered the task of directing to Tommy Lee Wallace, who had been so instrumental in the making of the first film and had expressed strong interest in directing a movie instead. But when Wallace refused, Carpenter instead approached American Film Institute graduate Rick Rosenthal, whose short The Toyer had made an impression on him. The two would suffer creative differences after Carpenter reshot various scenes to include more gore, much to Rosenthal’s annoyance, but the movie would become a success, holding its own against the likes of Friday the 13th Part 2.

In 1982, John Carpenter would become involved with the first remake of his career. Having been a Howard Hawks fan since he was a child, it was perhaps inevitable that he would at some point visit his idol’s work and make his own adaptation. A scene from The Thing from Another World had been used in Halloween, and so, after the success of Escape from New York, Carpenter was free to choose his next project. The Thing from Another World had been released by Hawks in 1951, at the height of the Cold War paranoia, and so its concept of an alien invader hiding among the people seemed to hit a nerve with cinema audiences in much the same way Invasion of the Body Snatchers would four years later. Directed by Christian Nyby and written by His Girl Friday’s Charles Lederer, the movie was based on John W. Campbell’s short story Who Goes There?, originally published in 1938 in an issue of Astounding Stories under the pseudonym Don A. Stuart, which dealt with a group of American scientists at an outpost in Antarctica who discover a deadly alien lifeform.

Universal Pictures would grant Carpenter his largest budget to date, $15m, based on a script by Burt Lancaster’s son, Bill. The project was first conceived when producer Stuart Cohen came across the short story in 1976, then bringing it to the attention of colleagues David Foster and Lawrence Turman. When it came time to hire a director, Cohen remembered Carpenter from his days at USC and was suitably impressed enough with his recent work that they offered him the job. To realise the groundbreaking special effects that would be required to do the concept justice, Carpenter once again approached Bottin, who he had collaborated with on The Fog two years earlier. For the main role of MacReady (spelt McCready in the story), the director contacted his Escape from New York star Kurt Russell, who had slowly become Carpenter’s on-screen alter ego. Filming commenced on August 24 1981 for three months, with photography taking the crew through such varied locations as Los Angeles and British Columbia. Bottin was overloaded with work due to the demands of the FX and so contacted Stan Winston to help with the canine transformation sequence.

Often referred to as the first in Carpenter’s ‘Apocalypse Trilogy,’ The Thing first surfaced on June 25 1982 and was a commercial failure, due to the release of the more family-orientated E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial two weeks later. Whereas Spielberg’s movie E.T. had a more optimistic tone, The Thing was a bleak and dark film that refused to offer a happy and straightforward ending. Eventually, it went on to make $13.7 during it theatrical run, less than its budget. But over the years, thanks to home video, The Thing slowly became a cult favourite among Carpenter’s fanbase and has since become considered his greatest work. It was tense, atmospheric and boasted possibly the best prosthetic effects of the 1980’s, and showcased the director’s talents as a master storyteller. After the financial disaster that The Thing suffered, Carpenter was unsure of his next move but was approached to adapt an upcoming novel by one of the most successful horror authors of all time.

By 1983, Stephen King had become one of the most adapted authors in the horror genre and had been an inspiration on such renowned works as Carrie, Salem’s Lot and The Shining. With respected Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg having recently directed a version of The Dead Zone, big names were starting to collaborate on King’s work. Richard Kobritz had scored a success by producing the TV mini-series Salem’s Lot when he received manuscripts from the author for his next two novels which he had expressed interest in having transformed into features. Declining Cujo, a tale about a rabid dog which turns on its owners, Kobritz instead chose to adapt Christine, which told of a nerdy teenager who develops a dangerous obsession with his new car. Having already worked with Carpenter on the 1978 TV movie Someone’s Watching Me, he approached the filmmaker about the possibility of developing King’s story. Kobritz hired writer Bill Phillips, whose only prior credit had been on the Henry Fonda TV drama Summer Solstice, to convert the novel into a screenplay while he raised the finance.

Christine was budgeted at around $10m. $500,000 of the total was allocated to the purchase of suitable cars, of which there would be twenty three. Despite Christine being described as a 1958 Plymouth Fury, the producers also purchased Belvederes and Savoys as well. After being customised to resemble the Fury, including being sprayed red and white, only sixteen of the cars were used during filming. Principal photography commenced on April 25 1983 in Santa Clarita, California, while the school scenes were shot at Oak Park High School. Originally, Kevin Bacon – who had scored a minor success with Friday the 13th and Diner a couple of years earlier, was in talks to portray the protagonist/antagonist Archie Cunningham, though he would eventually back out in favour of Footloose. Instead, the role went to twenty-two year old Keith Gordon, who been previously seen in Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill. Perhaps the film’s most impressive sequence is after a gang of bullies have near-destroyed Christine, only for her to slowly rebuild herself. This was achieved by the FX crew placing hydraulic pumps all around the car, under the body panels, and then causing it to compress and crush. Then, the footage was played back in reverse to give the illusion that the car was reforming. The book was published a mere four days after filming commenced, though the movie itself would not surface until 9 December 1983, grossing a little over $21m at the box office.

If Elvis had seemed a bizarre choice for the director of Halloween then his next project, Starman, would seem even more strange. Despite Carpenter having dabbled in the science fiction genre with both Escape from New York and The Thing, his work had usually contained a certain amount of cynicism, particularly towards authority. But Starman had more heart than any of his previous films, which may have alienated some fans but critics were impressed with the filmmaker’s newfound maturity. A couple of years back, Columbia had made the mistake of passing on the chance to finance and release E.T., which went on to become a record-breaking success. Studio head Frank Price had no intention of letting another potential cash cow pass by, so when actor Michael Douglas – who had produced such movies as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – approached him once again with the script for Starman he accepted. The screenplay, by Bruce A. Evans and Raynold Gideon, had been in circulation at Columbia for four years but after the success of Spielberg’s similarly hearted hit, Starman was finally rushed into production. During preparation, Price defected to Universal (who were responsible for E.T.), but Douglas kept the project alive, eventually offering the director’s chair to Carpenter after seeing his ability to manage action scenes in his previous work.

Once again, Kevin Bacon was rumoured to be in the running to play the title character, though the part would eventually fall to Jeff Bridges (who would be nominated for an Oscar for his troubles). As with most of Carpenter’s films, Starman would be a blend of several genres – road movie, science fiction and traditional love story. The production send the cast and crew across America, from New York and Washington to Arizona and Nashville. Roy Arbogast, who had previously worked with Carpenter on Escape from New York, The Thing and Christine, handled the impressive effects, while the task of creating the baby’s transformation fell to three separate artists – Rick Baker, Dick Smith and Stan Winston. Carpenter, who would usually score most of his movies, was replaced by Jack Nitzsche, who had developed a productive working relationship with Douglas. Starman was another success for the director and was well received by critics. A short-lived TV spin-off was produced in 1986, with Airplane! star Robert Hays in the role of the friendly alien.

With the tagline ‘A Film by John Carpenter’ alone being able to sell a picture, producers began to dust off his old scripts and adapt them into television movies. Black Moon Rising was originally to have been a Charles Bronson picture, but by the time it was developed a decade after Carpenter had sold the rights, Tommy Lee Jones had been hired instead. First time writers Gary Goldman and David Weinstein had written a Western back in 1982 called Big Trouble in Little China and had submitted it to producers Paul Monash and Keith Barish at Twentieth Century-Fox. Though impressed with the story, they felt that it needed work and asked them both to rework it and move the action to a modern day setting, but Goldman rejected the request. The two were jettisoned from the project and the producers brought it W.D. Richter, a script doctor who had also wrote the 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers to adapt the story as they had asked. Richter was contacted by Goldman, who suggested that he leave the project, but his attempts were futile and a workable script was finally submitted.

Further problems arose, however, when Fox wanted only Richter to receive a writing credit for the script. After much debate, the Writers Guild of America ignored their request and instead moved in favour of Goldman and Weinstein, opting to leave Richter’s name from off the film. When Carpenter was first offered the film in July 1985, he expressed concern over the script, but now it had been reworked by Richter (who, incidentally, was a student at USC the same time as Carpenter) he eventually agreed, redrafting the script himself by fleshing out the role of Gracie Law and removing certain sequences that would help reduce the budget. He saw the two protagonists, Law and Jack Burton, were very reminiscent of Howard Hawks characters, with quick-fire delivery much like in His Girl Friday and Bringing Up Baby. For the role of reluctant hero Jack, Carpenter knew of only one man who would be suitable – Kurt Russell. But with Paramount’s The Golden Child, which dabbled with similar themes, also in production at the same time and starring box office star Eddie Murphy, the studio wanted to hire Clint Eastwood. Luckily, the ageing star had prior commitments and Carpenter was able to give the part to Russell, who portrayed him as an Eastwood-type.

The experience of making Big Trouble in Little China was frustrating for Carpenter, as the large budget had meant that the studio were enforcing their will upon the usually independent director. When the film was released it failed to reach the producers’ expectations and Carpenter instead turned his back on Hollywood and returned to low budget filmmaking. After signing a multi-film deal with Alive Pictures, he began to develop his first script, a supernatural loosely inspired by the BBC TV series Quatermass called Prince of Darkness. Carpenter had first conceived the idea when researching atomic theory and theoretical physics and the story soon came together. One major influence during writing was The Stone Tape, a BBC 2 ghost story from 1972 by Nigel Kneale, from not only the basic premise but also some of the character and place names – Kneale University and Carpenter’s writing pseudonym, Martin Quatermass (after Kneale’s Quatermass and the Pit). This angered Kneale, who had insisted on having his name removed from the credits of Halloween 3: Season of the Witch after various creative disputes.

With a budget of $3m and full creative control, Carpenter began casting his movie, recruiting many of his regulars who had been unable to use during his last few projects. These included Donald Pleasence (Halloween, Escape from New York) along with Peter Jason, who would start his long-term working relationship with Carpenter here. Producer Shep Gordon suggested casting rock star Alice Cooper, whom he also managed, as well as including one of his songs on the soundtrack (which would later be released on Cooper’s album Raise Your Fist and Yell). He also brought one of his stage props for an impaling scene. In some ways, Prince of Darkness could be considered the end of Carpenter’s run of classic movies, as while it is far more stylish than his more recent output it lacks the genius of his earlier work. Despite a mixed reaction with critics, Prince of Darkness would make $14m during its run at the cinema and Alive immediately commissioned his next project.

Eight O’Clock in the Morning was a short story by writer and cartoonist Ray Nelson, first published in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction back in the 1960’s. It told of George Nada, an everyday man who stumbles upon the truth that society is being controlled by the ‘Fascinators.’ This provided the basis for Carpenter’s next screenplay, which he would write under the pseudonym Frank Armitage (named after a character from H.P. Lovecraft’s The Dunwich Horror). They Live follows a similar pattern of a nobody, simply called Nada (Spanish for ‘nothing’), who drifts into town and sees a society which has been split into two – the rich, middle class and the poor working class. Eventually, he comes to realise that this is all a ploy by a race of aliens who are keeping mankind docile in an effort to rule our world and use its resources. Their ‘true’ identities can only be seen by wearing special sunglasses, which strips away all the brain-washing metaphors that decorate capitalist America. Thus, the dollar sign is replaced by the slogan ‘This is Your God’ and billboards simply say ‘Consume’ and ‘Marry and Reproduce.’

The script first arouse as Carpenter had begun to watch television again, only to become disgusted by the commercialisation, where everything was designed to make the viewer spend their money and invest in products that they do not need. This was also the era of Reaganism, where greed and power were the only things that counted and the rich got richer as the poor died in the gutter. True capitalism at its purest! Carpenter was allocated $3m and set out to make his urban science fiction Western satire. For the role of Nada, Carpenter’s quintessential antihero, he chose professional wrestler Roddy Piper, whom he had first met back at WrestleMania III in 1987. They Live began filming on March 7th 1988 in downtown Los Angeles, eventually wrapping eight weeks later. Perhaps the most famous sequence from the movie was the five minute punch up between Piper and Keith David, who had made an impression on the director during the making of The Thing. The fight scene would mix boxing with wrestling moves, both performed by the actors without stuntmen. This is often considered Carpenter’s last great movie, and it would be another four years before he would direct again.

As he took a hiatus from filmmaking, another one of his early screenplays was adapted for television. El Diablo was a Western starring future ER star Anthony Edwards and Iron Eagle’s Louis Gossett, Jr. Produced by HBO, like many films based on his early work, much of the script was gutted and reduced to a generic TV movie, making its debut on July 22. Another script, Blood River, had originally been acquired by John Wayne’s company Batjac Productions as an intended vehicle for the star, though sadly he would pass away before this materialised. The role eventually went to Wilford Brimley and directed by television regular Mel Damski. When Ghostbusters director Ivan Reitman walked from the science fiction comedy Memoirs of an Invisible Man, Carpenter finally decided that it was time to return to filmmaking when he was approached by Warner Bros. to take over the project. It would mark his first dealing with a major studio since the unpleasant experience of Big Trouble in Little China and naturally Carpenter was hesitant, but he was also frustrated at having not made a movie in a few years, so eventually agreed.

The script had been adapted by Dana (The ‘burbs) Olsen, William (The Stepford Wives) Goldman and Robert Collector from a 1987 novel by H.F. Saint. Chevy Chase had been a major comedy star in the 1980’s with the likes of Fletch, National Lampoons Vacation and Caddyshack but by 1992 his light was starting to fade and Memoirs of an Invisible Man had been pitched as his major comeback. Knowing that the special effects of Chase’s invisibility would be nothing short of spectacular, the producers approached Industrial Light and Magic for assistance. With a budget of $40m, this was by far Carpenter’s most mainstream effort and he was well aware of the commercial pressure that he was under. The script had gone through several rewrites by Goldman in an attempt to move away from straightforward comedy and explore the mental state of the transparent protagonist. When Memoirs of an Invisible Man was released it proved to be a minor success, though it did little to boost Carpenter’s confidence and he once again retreated to low budget filmmaking.

Body Bags was yet another TV movie, but this time it offered a new challenge in the form of an anthology. Co-directed by Tobe Hooper (who had directed the masterpiece The Texas Chainsaw Massacre), this would provide Carpenter the rare chance to appear in front of the camera, where he would portray the narrating Coroner. Initially produced as a pilot episode for a TV show that was never commissioned, Body Bags would feature cameos by several respected names of the horror community, including directors Wes (A Nightmare on Elm Street) Craven, Sam (The Evil Dead) Raimi and Hooper. Other appearances come from singer Deborah Harry, FX artist Greg Nicotero, model Twiggy and Star Wars icon Mark Hamill. Showtime expressed no interest in continuing after three stories had been filmed so it was edited together into a movie.

Carpenter has cited various influences for the Body Bags format, including the creepy 1940’s British classic Dead of Night, George A. Romero’s Creepshow and Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors. The three tales on show here are of varying quality, with Carpenter handling two and Hooper directing the final one. Played more for laughs than terror, Body Bags was an enjoyable if disjointed affair which proved to be an enjoyable experience after Carpenter’s recent hit and miss career. It would have been interesting to see how this series would have progressed, with perhaps other respected directors directing further segments. Sadly, this was not to be and no further episodes were commissioned, even after the release of Body Bags. It was surprisingly how well received the anthology was received, even more so than his last few efforts, and gave fans a little reminded of what he was capable of when given the right project.

Carpenter would complete his ‘Apocalypse Trilogy’ (following The Thing and Prince of Darkness) with his 1995 horror In the Mouth of Madness, a love letter to both Stephen King and H.P. Lovecraft. Conceived by Michael De Luca, then president of production at New Line Cinema and the man responsible for the camp Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare script, Madness was full of surreal monsters and bizarre imagery. Taking its name from Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, De Luca’s story was an interesting commentary about the effects that violent art has on society and the pretentious nature of many successful authors. The project would see Carpenter reunite with Memories of an Invisible Man actor Sam Neill, who sometimes comes across more sinister than the man he is hunting. Other subtle references in the story was the town’s name of Hobb’s End, taken from an underground train station in Quatermass and the Pit.

In the Mouth of Madness was another example of Carpenter gathering together an impressive cast, which included German star Jürgen Prochnow (most famous for Das Boot), Charlton Heston, John Glover and David Warner. Principal photography lasted 36 days in and around Toronto, Ontario, Canada, which doubled for both New York and Hobb’s End. Carpenter had planned an ambitious ending where the entire town was sucked through into the darkness, but when Industrial Light and Magic stated that the budget would not be able to extend to accommodate for the effect, he was forced to rethink. The movie was released in America on the 3rd February 1995 and performed lower than expected. Had In the Mouth of Madness been produced ten years earlier then it would probably have been held in the same regard as his mid-’80’s output, but sadly the film soon made its way to video and failed to reignite his career.

Carpenter followed In the Mouth of Madness with Village of the Damned, a remake of the 1960 ‘demonic children’ chiller of the same name. Inspired by John Wyndham’s novel The Midwich Cuckoos, published three years earlier, Wolf Rilla’s creepy tale of a small British village besieged by strange children when the female population fall pregnant after mysteriously falling unconscious. Having already remade The Thing from Another World, which had since become a cult classic, Carpenter agreed to direct the script by David Himmelstein. Relocating the action from England to America, Superman star Christopher Reeve (in his last role before being paralysed in May 1995) took the lead role of Dr. Alan Chaffee, who tries to stop the village’s evil children from destroying their hometown of Midwich. Filmed in Inverness, Nicasio and Point Reyes, California (the latter being where some of The Fog was made) on a budget of $22m, Village of the Damned would co-star Cheers regular Kirsty Alley, Crocodile Dundee’s Linda Kozlowski and Mark Hamill.

Using much of the dialogue from Wyndham’s, the film’s main flaw was Himmelstein’s generic script. Rilla travelled over from Cannes, France, to visit the set for a few days to give Carpenter his blessing. The special effects were handled by several studios who Carpenter had previously collaborated with, including Industrial Light & Magic’s Bruce Nicholson (Memoirs of an Invisible Man), KNB EFX (In the Mouth of Madness) and Roy Arbogast (Starman). Originally, the children’s contact lenses were to have been designed by KNB but after fear of infection, the filmmakers instead opted for having them added in post production. Village of the Damned was another film of Carpenter’s films to be greeted with a mediocre response and critics began to speculate as to whether he had lost his magic or not. It had been over a decade since the likes of The Thing and his most recent offerings had been barely above average. After regular discussions with Kurt Russell, he decided to bring back one of his favourite characters.

Carpenter had originally developed a sequel for Snake Plissken back in 1985 prior to the release of Big Trouble in Little China, with a script written by Coleman Luck (The Equalizer). The idea would remain touched for a decade until the enthusiasm of his lead actor would convince him to create a sequel. Carpenter and Russell would write the screenplay together along with Hill for what was to become Escape from LA. Since the first movie, the character had become a favourite among fans and Escape from New York has one of his most popular films. But in the fifteen years that had passed since Snake’s first introduction, special effects had progressed considerably, including the invention of CGI. Following the Northridge earthquake in Reseda, San Fernando Valley on January 17 1994, the concept of Los Angeles breaking away from the continent was discussed. It is worth noting that this premise was originally created by the late comedian Bill Hicks, in which he referred to the City of Angeles as ‘Hell-A.’

Escape from LA is less a sequel to New York and more a remake. While it does briefly reference the original, it is basically the same story in a different location. This time, Snake is sent to the island of Los Angeles, a penal colony where the sinful are sent to keep ‘Moral America’ clean. The movie was budgeted at around $50m, more than seven times the amount of New York. The supporting cast was made up of various cult stars such as Steve (Reservoir Dogs) Buscemi, Pam (Jackie Brown) Grier, Peter (Easy Rider) Fonda and Bruce (The Evil Dead) Campbell. Despite its appeal, Escape from LA was yet another financial disappointment, making only $25.5m in the US, barely half the budget. There have been various rumours of further Snake escapades, from a proposed second sequel, Escape from Earth, to a possible remake that had both Len (Underworld) Wiseman and Jonathan (Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines) Mostow attached to direct.

Two years later, Carpenter would make his first (and, to date, only) vampire movie, which would mix gruesome prosthetic effects with an aggressive performance by the underrated James Woods. Loosely based on the 1991 novel Vampire$ by fantasy author John Steakley, Vampires would mix his favourite genre (Western) with his most popular (horror). The story focused on Jack Crow, a Vatican-sanctioned vampire hunter who travels across New Mexico destroying hives of ‘ghouls,’ until their Master, Valek (Thomas Ian Griffith), wipes out Crow’s team, leaving him and his sidekick, Montoya (Daniel Baldwin), to try and defeat the head vampire without the support of the church. While Carpenter has yet to make a Western, this is the closest he has come to it so far, from the desert setting to Crow, the typical Carpenter antihero.

Vampires was originally to have been directed by Russell Mulcahy, who opted instead to make the straight-to-video flop Talos the Mummy. Carpenter had contemplated not directing another feature again after the stress of Escape from LA until he was approached by Largo Entertainment to adapt Steakley’s novel. There were two scripts, one by Don Jakoby and another by Dan Mazur, which Carpenter would combine along with elements of the book to create his own original story. The budget was chopped by a third just before principal photography, meaning that the crew were forced to work at double speed in order to meet the demands of the studio. One scene in particularly proved a challenge for the filmmakers, where Valek and his ghouls arise from the ground. Refusing to use CGI, Carpenter had his cast buried under sand, with straws to allow them to breathe. Despite mixed reactions, renowned critic Gene Siskel commented that Woods should have been nominated for an Academy Award.

For his next project, Carpenter would almost go full circle back to the beginning of his career, by semi-remaking his commercial debut Assault on Precinct 13 as a science fiction Western. Recruiting a varied cast including Species actress Natasha Henstridge, rap star-turned-actor Ice Cube, British actor Jason Statham and Escape from LA’s Grier. Carpenter would once again recruit KNB to manage the special effects and the creation of his antagonist, simply called Big Daddy Mars. Much like Assault, Ghosts of Mars would see a cop and a criminal having to fight side-by-side to save themselves from an invading force. Ice Cube’s ‘Desolation’ Williams is an attempt to carbon copy ‘Napoleon’ Wilson, though sadly the rapper lacks a likeable screen presence. Obviously realising that vampires and even Snake Plissken cannot revive his career, Carpenter instead chose to return to his early work and start again.

The construction of his Mars set commenced in May 2000 in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with principal photography beginning on August 8th. With a budget of $28m, Carpenter had the Martian mining town of Shining Canyon designed from scratch. For the train scenes, the production moved to Rio Rancho, New Mexico, for two weeks before finishing off in Los Angeles. Filming finally ended in October, with its release almost a year later (August 24 2001). For the soundtrack, Carpenter decided to collaborate with various rock stars, including Anthrax, Buckethead and ex-Whitesnake guitarist Steve Vai. Once again, Carpenter’s film was met with critical disappointment, and its $3.5m opening weekend quickly diminished. Ghosts of Mars would see Carpenter semi-retire from the industry for several years, instead allowing a new generation of filmmakers to remake his back catalogue.

While his Vampires movie spawned a franchise of its own, Assault on Precinct was given a makeover by French director Jean-François Richet, making his American debut. The film starred Lawrence Fishburne and Ethan Hawke (as crook and cop, respectively), with crooked Gabriel Byrne attempting to kill them. Shortly after, Rupert (Stigmata) Wainwright helmed a new version of The Fog, a PG-13 disaster that even Carpenter had expressed disappointment with. Rock star Rob Zombie, who had made started his directing career with the low budget horror The House of 1000 Corpses, directed a successful yet shallow remake of Halloween for Dimension in 2009, with his sequel set for a release this August (though this is subject to change).

Carpenter would finally return to the director’s chair in 2005 with two episodes of the critically acclaimed series Masters of Horror. The first segment, Cigarette Burns, shares many similarities with his 1995 movie In the Mouth of Madness, in that they both make a comment on art’s effect on the human mind and whether or not it can influence real life violence. More recently, there have been several rumoured projects that would see Carpenter making his first feature film since 2001. The Ward sees an institutionalised woman being haunted by a supernatural presence while LA Gothic (from the writers of Dario Argento’s upcoming Giallo) is an anthology about an vengeful ex-priest trying to save his daughter from the horrors of Los Angeles. Two other possible projects include the Nicolas Cage vehicle Scared Straight and The Prince, though little is known about this project at present. It has been almost forty years since he first entered the movie industry and now it seems that John Carpenter may finally make his much anticipated and long-overdue return!

ARTICLE: Christian Sellers

6 Responses to SLASHER LEGEND – John Carpenter