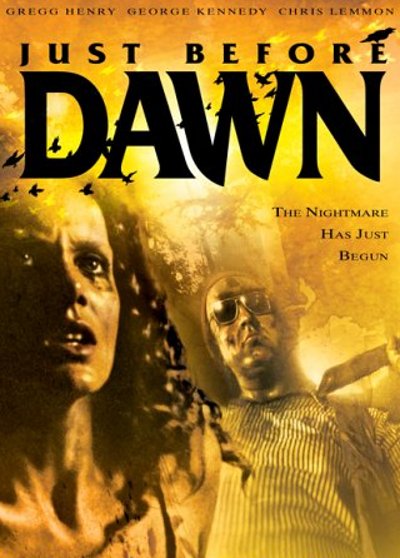

Of all the lost-in-the-wilderness slashers to appear in the early eighties (which would include The Final Terror and The Forest), Jeff Lieberman’s backwards thriller Just Before Dawn was arguable the most beautifully shot and well crafted, perfectly capturing the deadly beauty of the Oregon mountains. Having previously helmed the nature-run-amok flick Squirm, Lieberman had been hired by adult producer Jonas Middleton to re-write and direct a script by first-time writer Mark Arywitz entitled The Last Ritual. The resulting effort would be Just Before Dawn, which would take key elements from Arywitz’s premise and draw heavily from such classics as Deliverance and The Hills Have Eyes. Lieberman would deny that his movie was a slasher, indicating that the likes of Friday the 13th had not even been released as his own film was being shot, but regardless, Just Before Dawn is one of the most underrated slashers of its era.

Returning home from a day’s hunting, Ty (Mike Kellin) and his nephew, Vachel (Charles Bartlett), stop by at an abandoned church to finish off their beers. Whilst drinking at the later, Ty notices a silhouette pass over a hole in the roof and so heads outside to get a better look. Suddenly their pick-up truck rolls down the hill and crashes into a tree, bursting into flames. Vechel opens the door to see what the commotion is when from out of nowhere the figure (John Hunsaker) appears and attacks him with a saw. Moments later, Ty sees the shape leaving the church wearing Vachel’s clothes but soon realises what has happened and so escapes into the trees. Meanwhile, a group of friends are heading into the mountains to a property owned by the family of Warren (Gregg Henry). On his journey he is accompanied by girlfriend Constance (Deborah Benson), Daniel (Ralph Seymour), his brother Jonathan (Chris Lemmon) and Megan (Jamie Rose), Jonathan’s girlfriend.

Returning home from a day’s hunting, Ty (Mike Kellin) and his nephew, Vachel (Charles Bartlett), stop by at an abandoned church to finish off their beers. Whilst drinking at the later, Ty notices a silhouette pass over a hole in the roof and so heads outside to get a better look. Suddenly their pick-up truck rolls down the hill and crashes into a tree, bursting into flames. Vechel opens the door to see what the commotion is when from out of nowhere the figure (John Hunsaker) appears and attacks him with a saw. Moments later, Ty sees the shape leaving the church wearing Vachel’s clothes but soon realises what has happened and so escapes into the trees. Meanwhile, a group of friends are heading into the mountains to a property owned by the family of Warren (Gregg Henry). On his journey he is accompanied by girlfriend Constance (Deborah Benson), Daniel (Ralph Seymour), his brother Jonathan (Chris Lemmon) and Megan (Jamie Rose), Jonathan’s girlfriend.

On their travels they make various comments about incest and other clichés regarding country folk, before a deer suddenly runs out across the road in front of them. Further up into the mountains they come across Roy McLean (George Kennedy), a local forest ranger who warns them about straying too far into the woods. Ignoring him, they continue on their way, eventually stopping when Daniel hears a strange noise. As they head outside to investigate they find an eccentric and drunk Ty, who tries to get a lift from them but they refuse. But, as the van drives away, Ty notices that the figures has climbed on top. Realising that he is finally safe, he walks off in the opposite direction to enjoy his drink. Once they get to the end of the line, the group take what they need to hike through the mountains and set off, unaware that the killer has followed them.

That night, Constance, Daniel and Megan are settled around the campfire when they begin to hear noises from within the bushes. Scared of what may pounce out at them, Megan grabs a knife and challenges whoever is there to show themselves. A moment later, Warren and Jonathan appear from the trees, laughing at the joke they had played. The following day they see a young girl sat by the lake but as soon as she is made aware of their presence she runs away. Meanwhile, Roy find Ty who confesses about what happened to his nephew and, realising that the strangers are vacationing in the mountains, sets out to find them. The figure manages to track them down and, one by one, brutally slaughters them until only two survive, who eventually discover the truth behind the monster and the creepy locals.

That night, Constance, Daniel and Megan are settled around the campfire when they begin to hear noises from within the bushes. Scared of what may pounce out at them, Megan grabs a knife and challenges whoever is there to show themselves. A moment later, Warren and Jonathan appear from the trees, laughing at the joke they had played. The following day they see a young girl sat by the lake but as soon as she is made aware of their presence she runs away. Meanwhile, Roy find Ty who confesses about what happened to his nephew and, realising that the strangers are vacationing in the mountains, sets out to find them. The figure manages to track them down and, one by one, brutally slaughters them until only two survive, who eventually discover the truth behind the monster and the creepy locals.

Just Before Dawn is by far Lieberman’s most impressive work to date – well paced, tense and competently acted. Despite most of the cast being relatively unknown, the likes of Henry and Benson shine, particularly during the gruesome climax. The original script called for a bizarre snake ritual which was thankfully omitted during Lieberman’s re-writers (under the pseudonym Gregg Irving). The landscape, shot at Silver Falls State Park in Oregon, is breathtaking and becomes a character unto itself, a constant threat to the outsiders. Whilst the concept of city slickers lost in the woods is hardly original, the characterisation is far more impressive than, say, The Hills Have Eyes, and Lieberman’s refusal to follow the standard slasher formula of having invincible helps keep the story credible.

Despite hardly being a gory film, the action packed finale would be provided by FX artist Matthew W. Mungle and shot in the director’s back garden and is a true show-stopping moment. Benson’s progression from naïve young woman to brutal final girl is well realised and Henry provides a likable performance (he would later appear in the likes of Bates Motel and 24). Hunsaker plays the dual role of mutant killers adequately and Kennedy delivers the goods as usual. Comparisons to the likes of Deliverance are inevitable, with suburbanites straying away from the comforts of the city and paying the price for their ignorance, but Just Before Dawn manages to stand on its own two feet and, thanks to a talented cast and a smart director, what could have been just another slasher proves to be the best of its kind.

Despite hardly being a gory film, the action packed finale would be provided by FX artist Matthew W. Mungle and shot in the director’s back garden and is a true show-stopping moment. Benson’s progression from naïve young woman to brutal final girl is well realised and Henry provides a likable performance (he would later appear in the likes of Bates Motel and 24). Hunsaker plays the dual role of mutant killers adequately and Kennedy delivers the goods as usual. Comparisons to the likes of Deliverance are inevitable, with suburbanites straying away from the comforts of the city and paying the price for their ignorance, but Just Before Dawn manages to stand on its own two feet and, thanks to a talented cast and a smart director, what could have been just another slasher proves to be the best of its kind.

7 Responses to Just Before Dawn (1981) Review